|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Market Square (Reindeer Inn) |

|

Between 1644 and 1810, the site of the building that now stands at the corner of Market Square and High Street (No 2 Market Square – currently Bishop's Stortford Tourist Information Centre) was that of the Reindeer Inn.

It was built when the town was fast becoming a popular destination for travellers and was just one of several hostelries that sprang-up around the busy market place at that time (See Market Square). Its status as an inn also means it was offering alternative accommodation to the long established George Inn at the corner of North Street, and therefore would have been an extensive property. Travellers necessitated plenty of available rooms and their horses required good stabling.

How popular the Reindeer was at the start isn’t known, but its fortune and reputation certainly changed in the early 1660s when a new landlady arrived. She was the notorious Betty (Elizabeth) Aynsworth, who with her husband, Edward Aynsworth, soon established the Reindeer as a place of good ‘entertainment’.

Betty had originally lived in Cambridge where she was a noted procuress (meaning she was basically a pimp who employed prostitutes). There was nothing particularly unusual in her role at that time, but her unsavoury reputation didn’t go down too well with the university authorities and she was eventually banished from the city by the Vice Chancellor.

Whether or not her arrival in Bishop’s Stortford was by design or accident is open to debate, but there is little doubt she would have been fully aware of the town’s importance as a halfway-house for those travelling between London and the towns and cities of East Anglia, particularly Newmarket. Not only was Newmarket the site of Charles II’s country palace, it was also the home of horse racing and regularly attracted London’s gentry.

One contemporary chronicler wrote of Betty...’This famous lady has been carted out of Cambridge for a Bawd, then settled in Bishop’s Stortford and at length got into so good a plight as to entertain the nobility and foreign ambassadors between London and Newmarket, serving them in place with all the rarities desired.'

The most famous person known to have stayed at the Reindeer and partake in the ‘entertainment’ was the diarist Samuel Pepys, whose relationship with Betty (according to his diary) was a little more than platonic (see panel below).

|

|

Pepys's diary covered just ten years of his life (1659–1669), but wasn't published until over one hundred years after his death, and then not fully until 1970. Written in shorthand, it has been transcribed three times – the first in 1821 by Rev John Smith of St John's College, Cambridge. His transcription was then given to Richard Lord Braybrooke to edit, who in 1825 produced 'Diary and Correspondence of Samuel Pepys'. He added many footnotes, including this one: Pepys's diary covered just ten years of his life (1659–1669), but wasn't published until over one hundred years after his death, and then not fully until 1970. Written in shorthand, it has been transcribed three times – the first in 1821 by Rev John Smith of St John's College, Cambridge. His transcription was then given to Richard Lord Braybrooke to edit, who in 1825 produced 'Diary and Correspondence of Samuel Pepys'. He added many footnotes, including this one:

'Elizabeth Aynsworth, here mentioned, was a noted Procuress at Cambridge, banished from that town by the University authorities for her evil courses. She subsequently kept the Rein Deer Inn at Bishop's Stortford, at which the Vice-Chancellor and some of the heads of Colleges had occassion to sleep, in their way to London, and were nobly entertained, their supper being served off plate. The next morning their hostess refused to make any charge, saying that she was still indebted to the Vice-Chancellor, who by driving her out of Cambridge had made her fortune. No tradition of this woman has been preserved at Bishop's Stortford; but it appears from the register of that parish that she was buried there 26th March 1686. It is recorded in the History of Essex, iii. 130, 8vo., 1770, and in a pamphlet in the British Museum entitled 'Boteler's Case', that she was implicated in the murder of Captain Wade, a Hertfordshire gentleman, at Manuden, in Essex, and for which offence a person named [William] Boteler was executed at Chelmsford 10th September 1667, and that Mrs Aynesworth, tried at the same time as an accessory before the fact, was acquitted for want of evidence; though in her way to the jail she endeavoured to throw herself into the river, but was prevented.'

This implies that Betty's attempt to throw herself in the river occurred after she was acquitted, so we can only surmise it was a guilt related attempt to commit suicide. Whatever the reason her conscience seems to have been permanently clouded, for though she returned to the Reindeer, and perhaps continued her old ways, she also made a point of fraternising with local church members and managed to procure herself a Christian burial in St Michael's churchyard.

Braybrooke's footnote is certainly informative, but what is questionable is the actual year in which he states the trial took place – See below: THE TRIAL OF WILLIAM BOTELER

The Aynsworths were amongst the town traders who issued their own trading tokens in the 17th century – one bearing the name of Edward Aynsworth, worth a halfpenny, the other with a deer, chained, inscribed with the name of Elisabeth. Her name also lives on locally as Aynesworth Avenue, a small housing development off of the Stansted Road.

In 1881, former town historian J L Glasscock wrote: 'The Reindeer Inn stood on the site now occupied by the house of Robert Cole'. This implies that the inn was demolished after closure in 1810, and that the house shown in the photograph (above) taken in the mid 1800s, replaced it. That's not to say Robert Cole actually built the house, but in his ownership it was later converted into a shop. Under new ownership in the early 1900s it became a grocers named Walkers & Co Stores Ltd. The premises continued as a commercial outlet of one sort or another until 2009, at which time it became the town's tourist office

|

|

|

|

|

Samuel Pepys

|

|

|

|

|

|

Perhaps Betty Aynsworth’s most well known visitor was Samuel Pepys, who made several entries in his diary referring to the ‘Raynedeere’:

7th October 1667

: ..and before night did come to Bishop Stafford {sic}, to the Rayndeere - where Mrs Aynsworth (who lived heretofore at Cambridge and whom I knew better than they think for, doth live - it was that woman that, among other things, was great with my cosen Barmston of Cottenham, and did use to sing to him and did teach me ‘Full forty times over’, a very lewd song) doth live, a woman they are very well acquainted with, and is here what she was at Cambridge, and all goodfellows of the country come hither. We to supper and so to bed. And lay very well, but there was so much tearing company in the house, that we could not see my landlady, so I had no opportunity of renewing my old acquaintance with her. But here we slept very well.

23rd May 1668

: ..I with the boy Tom, whom I take with me, to the Bull in

Bishopsgate Street

and there about 6 took coach, and so away to Bishops

Stafford

{sic}, and there dine and change horses and coach at Mrs Aynsworth’s; but I took no knowledge of her. Here I hear Mrs Aynsworth is going to live at London; but I believe will be mistaken in it, for it will be found better for her to be chief where she is then to have little to do at London, there being many finer then she there.

By ‘taking no knowledge of her’ it would seem there may have have been some ‘falling out’ between Pepys and Betty because on his return journey from

Cambridge

he dined at the Boar’s Head in Windhill (See Guide 4).

26th May 1668

: .. and so about

noon

came to Bishop’s

Stafford

{sic} to another house then what we were at the other day, and better used; and here I paid for the reckoning 11s, we dining all together and pretty merry.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Murder of Captain William Wade

|

|

My curiosity as to Betty Aynsworth's 'implication' in the murder of Captain William Wade led me to a publication entitled: 'Boteler's case being an impartial narrative of the tryal, & penitent behaviour of Master UUilliam Boteler, executed September 10th at Chelmsford, about the murder of Capt. Wade : with the substance of a sermon preached on that occasion, and his last speech faithfully taken'. It must be one of the longest book titles on record!

A copy of the original book, or pamphlet, is in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, and also held on microfilm at Cambridge University Library (Rare Books Room – Classmark: B125:2.9.Reel 1712:5).

Not too many provincial murder trials were recorded in the 17th century unless they involved a person of some standing, so it would appear that the public interest shown in this particular case – in the form of a publication – was almost certainly due to two facts: 1) Captain Wade was the grandson of Sir William Waad (Wade), and 2) he was wrongly executed for the crime.

The book's narrative starts by outlining the case, then gives William Boteler’s ‘confession’ (verbatim) as told by him to the authorities and read out in court. It should be noted that at no point in his ‘confession’ does Boteler admit to the murder of Captain Wade, so perhaps his account of events should have been entitled ‘statement’. The text ends with a sermon preached at the trial and Boteler’s (very long) speech in which he reiterates his innocence but states he is happy to meet his death having been fairly and justly tried by English law.

Boteler’s articulate and detailed ‘confession’ certainly seems to be that of an innocent man, but the court heard only his side of events leading up to the murder. He could not properly defend the charge because the other man implicated in the crime, Robert Parsons, had by this time fled to Holland. As for Betty Aynsworth: it would ‘appear’ her only implication in the crime, as revealed by an apothecary, Mr Saunders, is that he overheard her say ‘Have you killed him then?’ She was acquitted of any involvement, but her attempt to commit suicide during (or possibly after) the trial does beg further questions.

William Boteler was born in Northamptonshire c.1650. He was well educated, did military service in France, and fought in battle at Senisse. On leaving the army he lived in the north of England but later travelled to London in search of work. There he met a man named Robert Parsons, described as ‘a person of debauched life and ill fame’, who he later made a point of avoiding.

Parsons was also acquainted with one *Captain William Wade, described briefly as ‘a gentleman of considerable quality’ and a captain of the *Train bands [sic].

*Trained Bands were local militia regiments, formed in 1572 during Elizabeth I’s reign for the defence of the realm. They were trained by expert soldiers specially hired for the task.

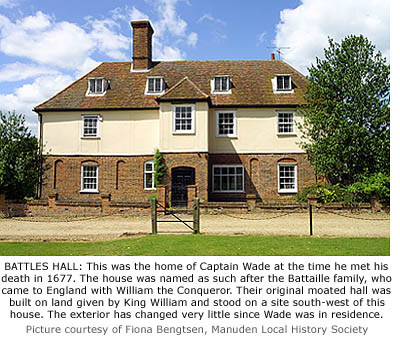

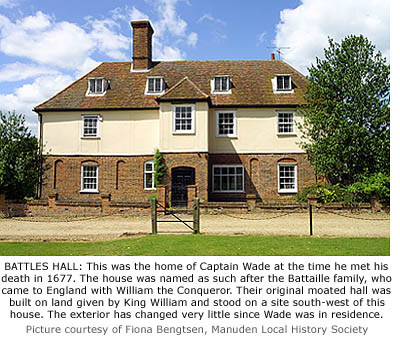

The two men’s backgrounds couldn’t have been more different, but they apparently became good friends and Wade often entertained Parsons at his home, Battles Hall, in Manuden, Essex. In July 1677, while visiting Wade’s house, a heated argument began over a wager whilst playing cards. Wade had previously lent money to Parsons and now refused to lend him any more. He called Parsons a thief or a highwayman, and after blows were exchanged Wade turned him out. It was while returning to London that Parsons meditated his revenge.

*The family name of Captain Wade was actually ‘Waad’, but pronounced ‘Wade’. The spelling was later changed to reflect the pronunciation. Captain Wade was the grandson of *Sir William Wadd (1546–1623), a most notable diplomat and officer of state in Elizabethan and Jacobean times, and his father was James Waad (Wade), son of Sir William and his second wife, Anne Browne (married 1599). William was born in October 1645 and at the age of 20 married Anne Barlee (daughter of Haynes Barlee of Clavering, Essex). They had two children: William born 1665, died 1686, aged 20, and Anne, died 1691 of smallpox, also aged 20.

The book then gives us Boteler's 'confession' as recorded by the authorities:

In it he relates that on the morning of Saturday 14 July 1677, he was visited at his London lodging house by a man named Parsons. He had made his acquaintance before, but on subsequent occasions had shunned him and declined his company on the grounds that he was generally thought of as nothing more than a common highway robber. On this occasion, Parsons suggested they ride to Bishop’s Stortford and stay at Mrs Ainsworth’s [sic] inn to get merry, and also to enjoy the country air. [It was probably by visiting Manuden that Parsons was familiar with Betty Aynsworth and the Reindeer Inn at Stortford – my brackets] Boteler at first refused this invitation but then agreed to ride with Parsons. It was during the journey north to Hertfordshire that Parsons told Boteler of the quarrel he’d had with Captain Wade, and that he wanted revenge in the form of a duel. He then asked Boteler if he would be his second, to which he refused. Boteler knew of Captain Wade, having often seen him in London, and told Parsons that a duel was not the answer. He then volunteered to help reconcile their differences with words alone.

They stayed Saturday and Sunday night at the Reindeer Inn and on the Monday morning Parsons ordered that their horses be made ready to ride, telling Boteler he would show him a pleasant neighbouring park. During the ride Parsons suggested visiting Captain Wade at his home in Manuden, some 4 miles north of Stortford, but then said he was afraid to visit in case his servants took advantage of him because of the previous argument. Boteler agreed to accompany him, but Parsons said it might be better if Boteler went to the house alone and spoke with Wade while he waited in a field near to the house. This Boteler agreed to.

On arrival at the house Boteler was warmly welcomed, even though Wade didn't know him, and drinks and converstion ensued. Boteler then explained his meeting with Parsons and the reason why he had come to the house. Wade replied that he was still unhappy with Parsons and that there was little hope of any reconciliation. When he asked where Parsons was, Boteler explained he was waiting in a nearby field because he feared the servants might do him harm. He also told Wade that Parsons had asked him to be his second in a duel with him, then confided his own dislike of Parsons saying he would rather act as Wade's second if a duel took place. Wade said he would go and meet with Parsons in the field and left taking his sword with him. At this point Boteler mounted his horse and rode off towards Bishop's Stortford, but within a short while was passed by Parsons riding at full gallop. As he did so he shouted ‘He is fallen’, and continued on towards the town. On arrival at the house Boteler was warmly welcomed, even though Wade didn't know him, and drinks and converstion ensued. Boteler then explained his meeting with Parsons and the reason why he had come to the house. Wade replied that he was still unhappy with Parsons and that there was little hope of any reconciliation. When he asked where Parsons was, Boteler explained he was waiting in a nearby field because he feared the servants might do him harm. He also told Wade that Parsons had asked him to be his second in a duel with him, then confided his own dislike of Parsons saying he would rather act as Wade's second if a duel took place. Wade said he would go and meet with Parsons in the field and left taking his sword with him. At this point Boteler mounted his horse and rode off towards Bishop's Stortford, but within a short while was passed by Parsons riding at full gallop. As he did so he shouted ‘He is fallen’, and continued on towards the town.

When Boteler arrived back at the Reindeer he found Betty Ainsworth crying upon a bed with Parsons standing nearby. As he entered the room she cried out ‘Oh! Mr Boteler, what have you done?’ On hearing this, Parsons swore that Boteler was not present when they fought, and if Wade was dead only he had killed him, fairly in a fight. Parsons then left the inn and rode off. With his departure, Boteler had ideas to stay a while longer at the Reindeer but when Mrs Ainsworth told him he should also leave, he did so.

Some 4 miles on towards London he met Parsons at a Smiths shop having his horse re-shod. They then rode on together and Boteler asked Parsons about the duel. He explained how they had begun a swordfight, but when Wade’s sword broke in two he started to flee. Parsons caught him and in the ensuing struggle got the better of him and asked if he would beg for his life. When Wade answered no, Parsons stabbed him the chest. He then stuck his blooded sword into the ground but as he did so it also broke, so he threw it into the undergrowth. On hearing this, Boteler suggested they should ride alone but Parsons insisted they should ride into London together. If questioned, he would explain that it was he who had killed Wade. They then continued together but Boteler said he kept back a fair distance. They reached the Green Man [Leytonstone], went across Hackney Marshes, and finally stopped at Parsons lodging house in Drury Lane. There he sent for some women he knew and told them of the duel. Boteler then left for his own lodging house.

The following day Boteler dined with friends and learned how he was being searched for by the Hue and Cry. He immediately went to Parsons lodging where he was told he had just missed him. Boteler was then advised to lodge elsewhere until Parsons was caught and so he went to friends house, an inn at Bloomsbury. There, during the night, the house was entered and he was seized while asleep by the constable and [night] watch. He protested his innocence but was taken to prison.

William Boteler stood trial at Chelmsford Assizes, and on Thursday 26 July 1677 was found guilty of murder and sentenced to death. He was hanged at Chelmsford 10 September 1677.

There does seem to be a contradiction regarding the actual year in which the murder of Captain Wade took place. Lord Braybrooke’s footnote in ‘Diary and Correspondence of Samuel Pepys’ (1825) states it happened in 1667, giving his reference as History of Essex, iii. 130, 8vo., 1770, and the pamphlet ‘Boteler’s Case.’ However, more detailed research by the Manuden Local History Society tells us that Wade’s daughter was born in 1671, and he didn’t take full possession of Battles Hall until 1674. Also, Boteler’s Case wasn’t published until 1678. Public interest in the case makes it unlikely the pamphlet was published eleven years after the event.

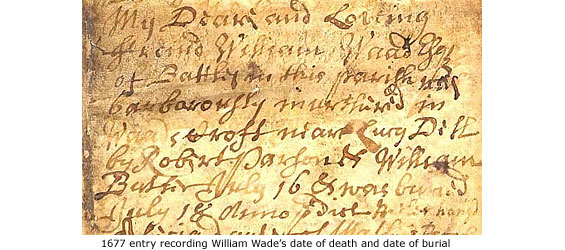

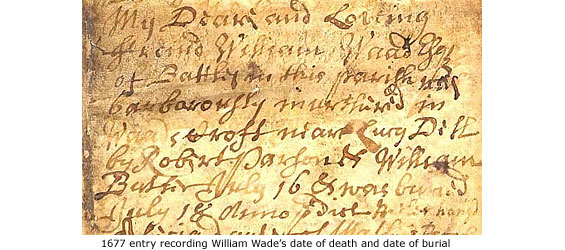

Absolute proof of the year William Wade died is found in a Manuden register (dated 1561–1733) of burials, baptisms, and marriages that is now available to be viewed at Essex Archives Seax website via this route>Essex Ancestors>Manuden parish>St Mary the Virgin>Image 40.

Under the date 1677 appears a rather personal entry, possibly written by the parish priest, that records more than just Wade's date of burial. Some of the hand writing is difficult to interpret but the content is fairly clear:

'My dear and loving friend William Waad ------ of Battles in this parish was barbarrously [sic] murdered in Waads croft ------ ------ ------ by Robert Parson & William [Boteler?] July 16 & was buried July 18 --------'

Information regarding the burial entry is thanks to Sarah Lynne.

Sir William Waad (Wade) died at Battles Hall in 1623 and was buried at Manuden church. His son, James, inherited the estate (one of several owned by Sir William), which eventually fell to his son, Captain William Wade.

*Robert Parsons escaped to Holland after the murder, but as a result of travelling to England in 1688 as part of the force gathered by William of Orange to save England from the prospect of having a future Catholic king, he received a full pardon for any earlier crimes.

*Additional information about Captain Wade and use of the photograph of Battles Hall at Manuden is thanks to Fiona Bengtsen of the Manuden Local History Society. A booklet giving the history of Battles Hall is available from Fiona: www.manuden.org.uk

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Trading Tokens

|

|

|

|

The issue of trading tokens in the town meant that Bishop’s Stortford was a place of commercial importance, and thirteen known examples were issued here – probably between 1665 and 1680. The first copper coinage issued in

England

was in 1613, when John Baron Harrington was granted a patent for issuing coinage farthings. His patent was renewed by Charles I but farthings were issued in such excessive quantities that by 1644 they were almost worthless. Parliament suppressed their issue but the patentees still encouraged circulation, giving 21 shillings in farthings for 20 shillings in silver. Copper money, although virtually valueless, flooded the country and nearly all gold and silver coinage disappeared. When farthings were originally suppressed, traders, without authority, issued their own tokens to be used as currency. The issue of trading tokens in the town meant that Bishop’s Stortford was a place of commercial importance, and thirteen known examples were issued here – probably between 1665 and 1680. The first copper coinage issued in

England

was in 1613, when John Baron Harrington was granted a patent for issuing coinage farthings. His patent was renewed by Charles I but farthings were issued in such excessive quantities that by 1644 they were almost worthless. Parliament suppressed their issue but the patentees still encouraged circulation, giving 21 shillings in farthings for 20 shillings in silver. Copper money, although virtually valueless, flooded the country and nearly all gold and silver coinage disappeared. When farthings were originally suppressed, traders, without authority, issued their own tokens to be used as currency.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[ BACK TO TOP ] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pepys's diary covered just ten years of his life (1659–1669), but wasn't published until over one hundred years after his death, and then not fully until 1970. Written in shorthand, it has been transcribed three times – the first in 1821 by Rev John Smith of St John's College, Cambridge. His transcription was then given to Richard Lord Braybrooke to edit, who in 1825 produced 'Diary and Correspondence of Samuel Pepys'. He added many footnotes, including this one:

Pepys's diary covered just ten years of his life (1659–1669), but wasn't published until over one hundred years after his death, and then not fully until 1970. Written in shorthand, it has been transcribed three times – the first in 1821 by Rev John Smith of St John's College, Cambridge. His transcription was then given to Richard Lord Braybrooke to edit, who in 1825 produced 'Diary and Correspondence of Samuel Pepys'. He added many footnotes, including this one: On arrival at the house Boteler was warmly welcomed, even though Wade didn't know him, and drinks and converstion ensued. Boteler then explained his meeting with Parsons and the reason why he had come to the house. Wade replied that he was still unhappy with Parsons and that there was little hope of any reconciliation. When he asked where Parsons was, Boteler explained he was waiting in a nearby field because he feared the servants might do him harm. He also told Wade that Parsons had asked him to be his second in a duel with him, then confided his own dislike of Parsons saying he would rather act as Wade's second if a duel took place. Wade said he would go and meet with Parsons in the field and left taking his sword with him. At this point Boteler mounted his horse and rode off towards Bishop's Stortford, but within a short while was passed by Parsons riding at full gallop. As he did so he shouted ‘He is fallen’, and continued on towards the town.

On arrival at the house Boteler was warmly welcomed, even though Wade didn't know him, and drinks and converstion ensued. Boteler then explained his meeting with Parsons and the reason why he had come to the house. Wade replied that he was still unhappy with Parsons and that there was little hope of any reconciliation. When he asked where Parsons was, Boteler explained he was waiting in a nearby field because he feared the servants might do him harm. He also told Wade that Parsons had asked him to be his second in a duel with him, then confided his own dislike of Parsons saying he would rather act as Wade's second if a duel took place. Wade said he would go and meet with Parsons in the field and left taking his sword with him. At this point Boteler mounted his horse and rode off towards Bishop's Stortford, but within a short while was passed by Parsons riding at full gallop. As he did so he shouted ‘He is fallen’, and continued on towards the town.

The issue of trading tokens in the town meant that Bishop’s Stortford was a place of commercial importance, and thirteen known examples were issued here – probably between 1665 and 1680. The first copper coinage issued in

The issue of trading tokens in the town meant that Bishop’s Stortford was a place of commercial importance, and thirteen known examples were issued here – probably between 1665 and 1680. The first copper coinage issued in