|

Julius Caeser's punitive expeditionary force to Britain in 55–54 BC was followed in 43 AD by a full scale Roman invasion. Under the guidance of Emperor Claudius the invasion force moved swiftly inland taking London, St Albans, and the tribal capital of Colchester. Within four years the south and the midlands were under Roman control, but the north and west took a little longer.

Despite Roman domination, guerrilla warfare continued for some twenty years after the invasion and in 60–61 AD the rebellious Queen Boudicca very nearly caused the occupying force to give up their new province. Roman arrogance and a misunderstanding was to blame for this violent episode in which Boudicca inflicted her bloody revenge, but under new management the Romans soon regained control.

To maintain speedy communications and rapid movement of soldiers and supplies, the Romans wasted no time in establishing a network of roads that criss-crossed Britain. This was no easy task, but occasionally their work was made easier by the groundwork already having been done for them. A good example of this is the Roman road between St Albans and Colchester, going via Braughing, which was based on an old Belgic track-way linking the two towns. That road (Stane Street) now forms the basis of the A120 between Colchester in the east and its junction with the A10 in the west – a stones throw from today's Braughing.

What the Romans called their roads is unknown, but some historians believe they were numbered. The ancient names of Watling Street, Ermine Street and Stane Street are very likely of Saxon origin – the word Street probably derived from the Road or 'Streat' names first mentioned by Edward the Confessor (1042–1066) in the making of laws for the safety of travellers. Stane Street may well have been called called 'Stone Street' in Edward's day.

Stane Street's existence in Bishop's Stortford had long been known, but the first substantial evidence of it came to light in 1976 during site clearance for the building of houses at, what is now, Legions Way. Excavations revealed a clear section of Roman road and its associated 'V' ditches running alongside, built shortly after the Romans arrived in the 1st century AD.

Locally the building of the town bypass has rudely interrupted Stane Street's original line, but it's still possible to trace its former route in Bishop's Stortford's modern day roads. From Dunmow Road in the east, near its junction with the M11, it cuts down via Parsonage Lane across the Meads and then climbs towards Little Hadham and Braughing via Galloway Road, Cricketfield Lane and Hadham Road.

The first indication of a Roman settlement here came in the early 1900s when a local historian, J.L. Glasscock, found evidence of a cremation cemetery in an old brickfield he owned on the eastern side of Stansted Road, opposite Cannons Close. It is also suggested that this brickworks may have been the site of a Roman tile-kiln.

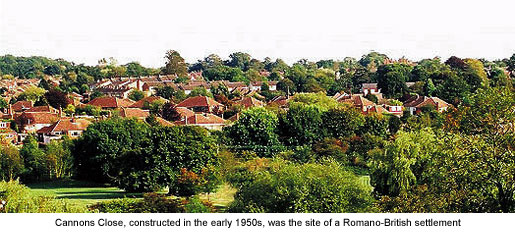

On the face of it there seems little or no reason for the Romans to have settled in this area, but from a military point of view its geographical position was important. In the early years of occupation there was a need to guard against insurgency, and a temporary wooden fort may have been built to control access to the (Stort) valley (possibly on the site of what was later to become Waytemore Castle). No evidence of a Roman fortification has ever been found but during the development of Cannons Close housing estate in the 1950s, excavations did reveal a substantial Romano-British settlement.

Positioned on high ground above the flood plain of the Meads, this settlement had not been established at random but had probably grown up around an Imperial posting station alongside Stane Street. Such stations were generally built midway between important towns for use as soldiers' rest houses, and Stortford does lie approximately midway between St Albans and Colchester.

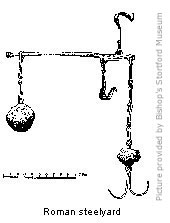

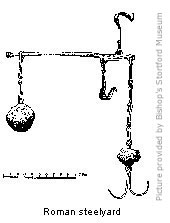

Coins found indicated a Roman presence from the 1st century AD through to the early 5th century, these dates confirmed by the styles of pottery also found. Other items initially unearthed were well preserved iron work, door latches, beams of weighing scales, knives and nails. Later finds included a gold ring (which then mysteriously disappeared) and a Roman steelyard (small weighing device).

The most important discovery made was building foundations of the second century, but with little co-operation between archaeologist and the developer no plans of the site were ever made, making it impossible to make even a tentative reconstruction. Where excavations were permitted, further finds included a small pipeclay figurine of Venus, indicating the religious life of the times. Such an object would have been placed in a small private shrine in a house together with other gods the Romans wished to venerate. Pagan religions in the Roman Empire gradually gave way to Christianity after 200 AD, and one particular find leads us to believe there were Christians in the settlement. The most important discovery made was building foundations of the second century, but with little co-operation between archaeologist and the developer no plans of the site were ever made, making it impossible to make even a tentative reconstruction. Where excavations were permitted, further finds included a small pipeclay figurine of Venus, indicating the religious life of the times. Such an object would have been placed in a small private shrine in a house together with other gods the Romans wished to venerate. Pagan religions in the Roman Empire gradually gave way to Christianity after 200 AD, and one particular find leads us to believe there were Christians in the settlement.

In 1956, on the site of the pavement outside Nos 174 and 175 Cannons Close, a burial was discovered; the body of a man wrapped in a shroud and laid within a stone coffin. Wet gypsum had been poured into the coffin to solidify around the body, which, on hardening, set into an exact form of the shroud. The shroud had since rotted but its impression could be clearly seen. Gypsum burials without grave goods were a common Christian practice in the Catacomb of Rome during the 2nd century. The man's age was put at about 50 years and he must have been of some social standing as the coffin, weighing some 2 1/2 tons (2,500kg), was made of Shelly limestone from Barnack in Northamptonshire. In medieval times this type of stone was greatly prized for the building of castles and cathedrals.

A further indication as to the size of the settlement came in the early 1970s when minor excavation work at Grange Paddocks revealed a Roman rubbish pit close to the river (See Guide 7 – Grange Paddocks). The settlement was probably abandoned around 410 AD when barbarian tribes threatened the Roman Empire in Europe and all of its armies were recalled to Rome.

It is questioned why the Romans chose to settle in this part and not a half-mile further south where the river was much easier to cross. After all, a ford had been established in pre-Roman times and was on the line of the Belgic track-way on which the Roman road (Stane Street) was based. The explanation for this is relatively simple.

The Romans worked on the principal that the quickest route between two points is in a straight line, and Stane Street was built in the straightest line possible, regardless of obstacles. It would certainly have been easier for soldiers and supply wagons to cross the river further south, but that would have meant changing the line of the road. The fact that excavations have never revealed bridge foundations where Stane Street crossed the river at the Meads, makes it likely that a temporary wooden structure was put in place at this point. Either that or legionnaires just waded through the water to cool their aching feet!

The Romano-British didn't dwell solely on the Meads. In 1962 a second Roman stone coffin was discovered on the north side of Dunmow Road, and a Roman cremation burial was found at Thornbera Road, south of the town. At Thorley, traces of a building (probably a farm) were discovered in a field south-east of Thorley church, and in 1980 development of new houses some 900 metres north of the same church revealed a Romano-British site of 3rd and 4th century origin. Excavations yielded roof tiles, nails and an extensive collection of pottery.

The Saxons who arrived in the 5th century had no desire to inhabit established Roman settlements, and in Stortford they chose to settle further downstream in the vicinity of, what is today, North Street. In the centuries that followed, masonry from the Romano-British settlement was dismantled and put to other uses, and what remained was swallowed up by nature's natural process. The reason why no large structural Roman remains have ever been visible here is because the settlement was primarily a posting station and had no civic amenities.

So, after nearly 400 years of occupation, what did the Romans actually do for Bishop's Stortford? The short answer is nothing. Unlike many of today's towns and cities, the foundations of which are formed with Roman bricks and mortar, Bishop's Stortford's roots lie firmly with the Saxons. The Romano-British settlement near the Meads was first and foremost an *Imperial posting station. What we do have to thank the Romans for is their roads, because without doubt it was these, specifically Stane Street, that ultimately led the invading Saxons into the Stort Valley.

*Amenities such as posting stations were only allowed to officials on Imperial business. Even the governor of the province had to ask the Emperor's permission to use such a post if it wasn't for military purposes.

|

The most important discovery made was building foundations of the second century, but with little co-operation between archaeologist and the developer no plans of the site were ever made, making it impossible to make even a tentative reconstruction. Where excavations were permitted, further finds included a small pipeclay figurine of Venus, indicating the religious life of the times. Such an object would have been placed in a small private shrine in a house together with other gods the Romans wished to venerate. Pagan religions in the Roman Empire gradually gave way to Christianity after 200 AD, and one particular find leads us to believe there were Christians in the settlement.

The most important discovery made was building foundations of the second century, but with little co-operation between archaeologist and the developer no plans of the site were ever made, making it impossible to make even a tentative reconstruction. Where excavations were permitted, further finds included a small pipeclay figurine of Venus, indicating the religious life of the times. Such an object would have been placed in a small private shrine in a house together with other gods the Romans wished to venerate. Pagan religions in the Roman Empire gradually gave way to Christianity after 200 AD, and one particular find leads us to believe there were Christians in the settlement.