|

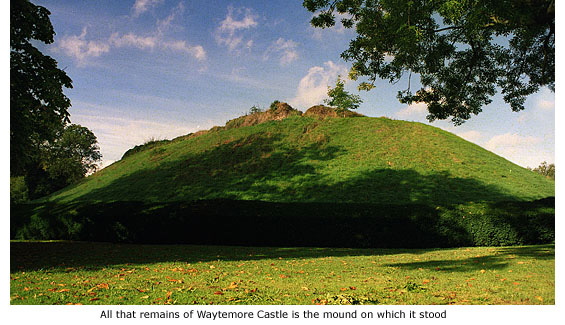

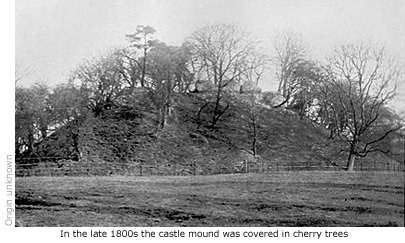

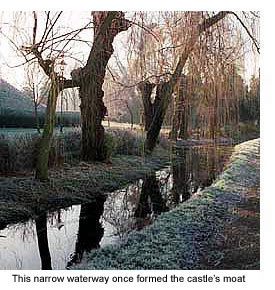

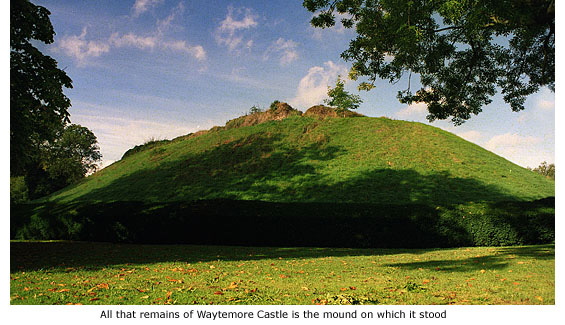

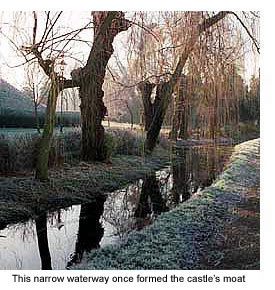

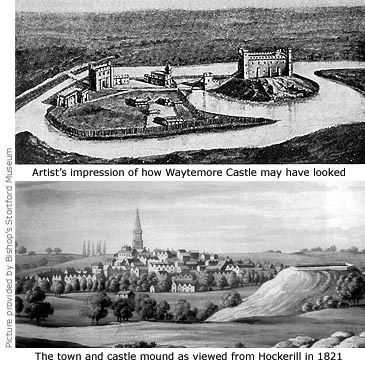

Opposite Charrington House is Castle Gardens, entered by either of two footbridges that span the narrow stream running alongside the road. Although somewhat reduced in size, this waterway once formed part of the outer moat of Waytemore Castle as built by the Normans. Unfortunately, all that now remains of the castle is the large earth mound on which it stood and a few remnants of wall from a later construction at its summit.

There are a number of mysteries surrounding the origin of Waytemore Castle, as well as the mound on which it stood, and in truth its actual beginnings may never be determined. Some historians believe the mound began as a Celtic barrow, or grave mound, while others think it was a Saxon ‘buhr’ i.e. a moated and stockaded fortress adapted early in the 10th century by Edward the Elder as a defence against the invading Danes.

This was the time of division in England between the House of Wessex in the south and south-west, and the Viking Danelaw in the north-east. The boundary line was the river Lea and Watling Street and in 913 Edward built a castle at Hertford as a frontier base for the re-conquest of Danelaw.

Further strongholds were built along the boundary line and, in theory, a defensive fortress at Stortford would have effectively blocked the Stort Valley gap thereby preventing infiltration by the Danes. Further strongholds were built along the boundary line and, in theory, a defensive fortress at Stortford would have effectively blocked the Stort Valley gap thereby preventing infiltration by the Danes.

It has always been thought that Waytemore Castle got its name from the very nature of its situation; the word ‘Wayte’ thought to be Saxon, meaning a place of ambush, and ‘more’ meaning a ‘fen or marsh’. However, there is now a suggestion that this translation meaning 'place of ambush in a marsh' is incorrect. Historian Jacqueline Cooper thinks it more likely that 'waite' is a corruption of 'thwaite', taken from an Old Norse word which has no English equivilant, and actually means 'forest clearing'. The word 'marr' is another Old Norse word, meaning 'boggy place'. If so, then this suggests that the later built Norman castle was built on an earlier site that was cleared out of damp woodland.

However, in King William’s Domesday survey of 1086, which documents virtually every town, village, manor and landowner’s possession in England, it’s somewhat surprising to find that Bishop’s Stortford’s castle isn’t recorded. This fact has naturally led some historians to believe that a castle didn’t exist here at all before the Conquest, but there is evidence to suggests otherwise.

After 1066 the Normans still met with formidable Saxon resistance, most notably in 1069 when the Lincolnshire nobleman Hereward the Wake led a rebellion from his base in the fens around Ely. Resisitance finally collapsed in 1071 after Hereward's ally, the Danish King Swein, made a separate peace with King William. To deter any further uprisings among the population the Normans then built temporary wooden castles on huge earth mounds at key points throughout the country. This tactic had previously been used by the Romans to quickly suppress the population of countries they conquered and could well have been employed by the Normans at Stortford.

If this was the case, then a fortress of some description must surely have been in place here by 1086. The strongest evidence of a castle at Stortford, however, comes from a document issued by King William himself.

When bishop William bought the Saxon manor of Stortford around 1060, it ultimately became the property of the See of London and remained therein after William’s death in 1075. Hugh de Oval succeeded him as bishop but when he died ten years later, King William granted the manor to his Chaplain and Chancellor, Maurice, and the following year (1086) ordained him as a priest and made him Bishop of London. When bishop William bought the Saxon manor of Stortford around 1060, it ultimately became the property of the See of London and remained therein after William’s death in 1075. Hugh de Oval succeeded him as bishop but when he died ten years later, King William granted the manor to his Chaplain and Chancellor, Maurice, and the following year (1086) ordained him as a priest and made him Bishop of London.

To mark this occasion the King issued a writ to his people in Anglo-Saxon, a part of which read ‘I would have you know that I have given to Maurice, Bishop of London, the castle of Stortford and all land that bishop William held of me formerly...’ We will never know whether the castle was the subject of an oversight by the king’s officials or deliberately omitted from Domesday Book, but this statement alone proves that a castle was certainly in existence here at the time of its compilation.

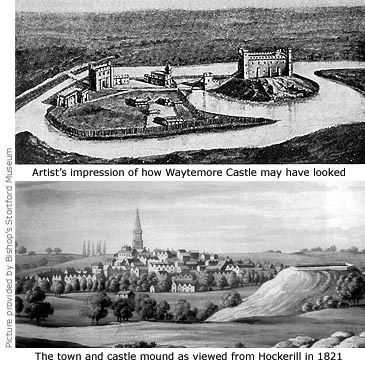

Norman built, or Saxon, the transition of Stortford’s wooden fortress to masonry castle would probably have taken place soon after 1086, although it’s thought the keep wasn’t constructed before 1135. The earth mound (pre-Norman or not) became the foundation for their familiar motte (mound) and bailey (courtyard) castle and its siting in the valley, as opposed to the usual high ground, was a deliberate move to command the important river crossing.

The 42ft (12.6m) high mound was surrounded by a moat and its top protected by a curtain wall of flint and rubble some 9ft (3m) thick. The later built keep, probably some 60–70ft (21m) high, stood within this wall and to add to its prominence, and remind Saxon inhabitants of the town and surrounding areas of Norman power and conquest, its exterior walls were probably painted white with a mixture of lime and chalk. The discovery of foundations consisting of flint and rubble suggest it was rectangular in shape, but while three of its sides were straight, the northern end was convex and bonded irregularly, in parts, with Roman bricks and medieval tiles.

At the south end of the mound was the gatehouse and steps that led down to the barbican (outer gate) where a drawbridge crossed the inner moat to the courtyard (bailey). This area of around four acres (now Castle Gardens) would have housed stables, storehouses, a blacksmith's shop, carpenters, and quarters for the garrison. The courtyard was protected by an outer moat and enclosed by a wall with two gatehouses, one of which would have given entrance from the garrison to the keep via the barbican. The second, secured by a drawbridge, would have led to the causeway.

With its natural defence of the river and marshy ground of the Meads it was a formidable stronghold. Inside the mound there still exists a well, sunk to a depth of 60ft (18m), from which water could be drawn from the marsh below if ever the castle came under siege.

According to the book Twenty Centuries of England Being the Annals of Bishop’s Stortford, only once did this happen when, in 1137, it was seized briefly by Anselm, Abbot of the rich Abbey of St Edmund in Suffolk, as a preliminary move to acquiring the Bishopric of London. However, his election by a faction in opposition to the dean was annulled shortly afterwards and he quickly retreated back to whence he came.

Waytemore Castle was a royal fortress, a prison and a private residence of the lord of the manor i.e. the bishop of London, though there is little evidence to suggest any bishop ever actually lived in the castle. They did, however, use it for the Bishop’s Court where any local felony of a religious nature was dealt with. To pay for this court, as well as the castle’s upkeep and defence, tenants of the manor were expected to do duty as castle guards or, in lieu of service, pay money to the bishop. Many took the latter option and the court rolls reveal many examples. Among them: Manor of Hadham Hall, 19s. 6d. (95p); Manor of Albury, £1. 1s. 0d. (110p); Somers in Rye Street 3s. 4d.(32p); and Read’s farm in Rye Street 3s. 4d. (32p). Waytemore Castle was a royal fortress, a prison and a private residence of the lord of the manor i.e. the bishop of London, though there is little evidence to suggest any bishop ever actually lived in the castle. They did, however, use it for the Bishop’s Court where any local felony of a religious nature was dealt with. To pay for this court, as well as the castle’s upkeep and defence, tenants of the manor were expected to do duty as castle guards or, in lieu of service, pay money to the bishop. Many took the latter option and the court rolls reveal many examples. Among them: Manor of Hadham Hall, 19s. 6d. (95p); Manor of Albury, £1. 1s. 0d. (110p); Somers in Rye Street 3s. 4d.(32p); and Read’s farm in Rye Street 3s. 4d. (32p).

In the 12th century Waytemore Castle became a pawn in a hotly contested fight for the crown of England, the beginings of which stemmed back to 1120 when Henry I’s only son drowned in a shipwreck. His daughter, Maud (Matilda), was declared rightful heir to the throne but within weeks of Henry’s death in 1135, his nephew, Stephen, set out to usurp her. With no wish to be ruled by a Queen the barons strongly supported him, as did the Church – albeit aided and abetted by Stephen's brother Henry, the Bishop of Winchester. In the event, Stephen was crowned King and Matilda was exiled in France.

The first two and a half years of Stephen's reign was peaceful enough but when his closest ally, Robert of Gloucester, decided to join Matilda’s cause, Stephen began to alienate many who were closest to him. Matilda, confident in the knowledge she now had enough support from the Church to be made Queen, returned from exile in 1139. But with two rival courts in England, civil war became inevitable.

To gain added support, Matilda promised the castle at Stortford to Geoffrey de Manderville II, Sheriff of Essex, if he would assist her against Stephen. If he didn’t she said she would destroy the castle. Manderville readily agreed. He already owned the manor of Thorley and the castle and town of Saffron Walden, and knew that if Stortford remained in hostile hands, travelling and communication between the two towns would become somewhat difficult.

The one disapproving voice in the equation was Robert de Sigillo the bishop of London, who not only owned the castle but also supported Stephen. He refused to be persuaded to give up either the town of Stortford or its castle for her cause, but in the quickly changing events of the time the castle became less important and the threat of destruction was never carried out. Matilda finally gained charge of England in 1141 after Stephen was captured at Lincoln, but she remained uncrowned for almost a year and Stephen eventually regained the throne.

Waytemore Castle was once again party to national events when a religious quarrel ensued between King John (1199-1216) and Pope Innocent III after the death, in 1205, of Hubert Walter the Archbishop of Canterbury. As his successor the King nominated John de Gray, Bishop of Norwich, but was greatly offended by the Bishop of London, William de St Mere l’Eglise, who, together with two other bishops nominated Cardinal Stephen Langton, whom the Pope accepted.

Angered that his own nomination had been ignored, King John retaliated by seizing Church lands, including the manor of Stortford, to which the Pope responded by threatening to lay England under an interdict – in effect banning all church services. Undeterred, King John seized even more Church property and in a further response the Pope served the interdict on England and excommunicated the King himself in 1208. As a consequence, Bishop William, who published the interdict, was obliged to leave the country and King John had his castle at Stortford dismantled. To add insult to injury he then created the town a Borough, freeing it from Church ownership.

Despite his actions King John had ultimately been defeated, but he was a canny man and his ‘political genius’ soon turned defeat into triumph by offering to make England a fief of the Papacy and pay homage to the Pope as his feudal lord. Pope Innocent III readily accepted the sovereignty of England and the king’s penance, forgave him and then returned the sovereignty to him with his blessing.

As a result of this the Bishop of London was reinstated and in 1214 King John was forced to rebuild the castle at his own expense. He visited the town on 29 March 1216, possibly to see for himself the progress being made in the rebuilding, but stayed in the castle for just one night. He died later that same year.

In the reign of Edward III (1327–1377) the castle was put in good repair. Wrought stone was used for doorways and leaded lights for windows and, under licence granted by Edward III to Ralph de Stratford, bishop of London, the castle was crenalated (fortified) and a chantry of secular priests, governed by the provost, founded in the chapel of St Paul’s within the castle courtyard. The priests were to live in the castle and pray regularly for the souls of Queen Philippa (Edward’s wife) and the bishop. In the reign of Edward III (1327–1377) the castle was put in good repair. Wrought stone was used for doorways and leaded lights for windows and, under licence granted by Edward III to Ralph de Stratford, bishop of London, the castle was crenalated (fortified) and a chantry of secular priests, governed by the provost, founded in the chapel of St Paul’s within the castle courtyard. The priests were to live in the castle and pray regularly for the souls of Queen Philippa (Edward’s wife) and the bishop.

By the 15th century Waytemore Castle was no longer deemed necessary as a defensive stronghold and rapidly fell into disrepair. Despite this, castle dues were still being paid during Elizabeth I’s reign but by 1545 the Bishop’s Court had moved to the Crown Inn at Hockerill (See Guide 9) and the ruiness castle was pulled down. The bishop’s prison and castle gatehouse survived for another hundred years but both were demolished under the Commonwealth confiscations in 1649.

The remnants of wall that remain at the mound’s summit are those of the castle keep rebuilt by King John in 1214. The original well in the south-west corner is covered by a large steel plate.

The mound has never been properly excavated, although an investigation in 1850 did revealed parts of the existing wall and a few human bones. A local historian of the time, J.L. Glasscock, made further minor attempts at excavation in 1900 but found only a few Roman coins of the Lower Empire. The most informative find was the accidental discovery in the late 1990s, within the grounds, of a large number of human bones which, experts say, strongly suggests there may have been some kind of medieval hospital attached to the castle. MORE PICTURES

|

Further strongholds were built along the boundary line and, in theory, a defensive fortress at Stortford would have effectively blocked the Stort Valley gap thereby preventing infiltration by the Danes.

Further strongholds were built along the boundary line and, in theory, a defensive fortress at Stortford would have effectively blocked the Stort Valley gap thereby preventing infiltration by the Danes. When bishop William bought the Saxon manor of Stortford around 1060, it ultimately became the property of the See of London and remained therein after William’s death in 1075. Hugh de Oval succeeded him as bishop but when he died ten years later, King William granted the manor to his Chaplain and Chancellor, Maurice, and the following year (1086) ordained him as a priest and made him Bishop of London.

When bishop William bought the Saxon manor of Stortford around 1060, it ultimately became the property of the See of London and remained therein after William’s death in 1075. Hugh de Oval succeeded him as bishop but when he died ten years later, King William granted the manor to his Chaplain and Chancellor, Maurice, and the following year (1086) ordained him as a priest and made him Bishop of London. Waytemore Castle was a royal fortress, a prison and a private residence of the lord of the manor i.e. the bishop of London, though there is little evidence to suggest any bishop ever actually lived in the castle. They did, however, use it for the Bishop’s Court where any local felony of a religious nature was dealt with. To pay for this court, as well as the castle’s upkeep and defence, tenants of the manor were expected to do duty as castle guards or, in lieu of service, pay money to the bishop. Many took the latter option and the court rolls reveal many examples. Among them: Manor of Hadham Hall, 19s. 6d. (95p); Manor of Albury, £1. 1s. 0d. (110p); Somers in Rye Street 3s. 4d.(32p); and Read’s farm in Rye Street 3s. 4d. (32p).

Waytemore Castle was a royal fortress, a prison and a private residence of the lord of the manor i.e. the bishop of London, though there is little evidence to suggest any bishop ever actually lived in the castle. They did, however, use it for the Bishop’s Court where any local felony of a religious nature was dealt with. To pay for this court, as well as the castle’s upkeep and defence, tenants of the manor were expected to do duty as castle guards or, in lieu of service, pay money to the bishop. Many took the latter option and the court rolls reveal many examples. Among them: Manor of Hadham Hall, 19s. 6d. (95p); Manor of Albury, £1. 1s. 0d. (110p); Somers in Rye Street 3s. 4d.(32p); and Read’s farm in Rye Street 3s. 4d. (32p). In the reign of Edward III (1327–1377) the castle was put in good repair. Wrought stone was used for doorways and leaded lights for windows and, under licence granted by Edward III to Ralph de Stratford, bishop of London, the castle was crenalated (fortified) and a chantry of secular priests, governed by the provost, founded in the chapel of St Paul’s within the castle courtyard. The priests were to live in the castle and pray regularly for the souls of Queen Philippa (Edward’s wife) and the bishop.

In the reign of Edward III (1327–1377) the castle was put in good repair. Wrought stone was used for doorways and leaded lights for windows and, under licence granted by Edward III to Ralph de Stratford, bishop of London, the castle was crenalated (fortified) and a chantry of secular priests, governed by the provost, founded in the chapel of St Paul’s within the castle courtyard. The priests were to live in the castle and pray regularly for the souls of Queen Philippa (Edward’s wife) and the bishop.