|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Corn Exchange |

|

The French Revolution (1789-1799) saw the overthrow of the French monachy in favour of a Republic and gave rise, in 1799, to Napoleon Bonaparte. He promptly returned France to dictatorial rule – declaring himself Emperor in 1804 – and then set out on a quest to conquer Europe and Britain in what became known as the Napoleonic Wars (1804-1815).

But his plans to invade Britain were effectively ended in July 1805 when the Royal Navy outmanoeuvred his fleets at Cape Finisterre off the northwest coast of Spain. Any further thoughts of invasion were finally quashed in October that same year when Nelson defeated the combined French and Spanish fleets at the Battle of Trafalgar. However, in the build-up to invasion Britain had been unable to import wheat from Europe. This inevitably led to an expansion of British wheat farming and, subsequently, higher bread prices. Farmers and landowners profitted greatly but feared once the French wars ended, the resumption of imported wheat would lower prices.

To protect their profits they put pressure on parliament to introduce a duty on imported wheat, and in 1815 a Corn Law was introduced stipulating that no wheat could be imported until domestic wheat cost £4 per quarter. Naturally the price was kept artificially high, but the subsequent increase in food prices caused people to spend far more on food than on other commodities, and the economy suffered. But since the vast majority of voters and members of parliament were landowners, the government was unwilling to consider new legislation to help the economy, or the poor.

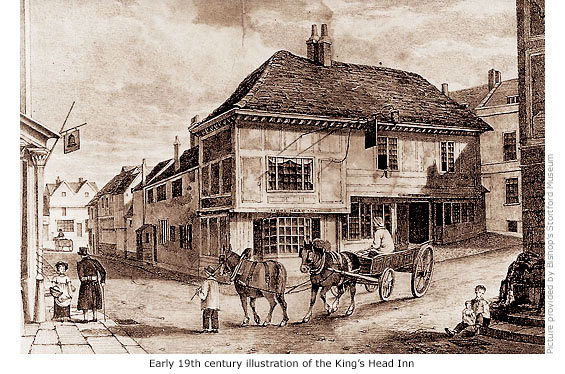

In 1821 Bishop’s Stortford’s population of 3,358 were suffering the effects of the *Corn Laws like everybody else, more so the working classes who struggled to feed their families. Of more pressing concern to local farmers and landowners, however, was that Wheat Hill (now High Street), where grain had been traded since the Middle Ages, was now proving unsuitable for the task. As a result of the flourishing wheat trade corn exchanges were being built in towns and cities throughout the country, and in 1828 a consortium of local businessmen put together a plan to build a corn exchange in Bishop’s Stortford. The site chosen was that of the King’s Head Inn in the market place.

In 1821 Bishop’s Stortford’s population of 3,358 were suffering the effects of the *Corn Laws like everybody else, more so the working classes who struggled to feed their families. Of more pressing concern to local farmers and landowners, however, was that Wheat Hill (now High Street), where grain had been traded since the Middle Ages, was now proving unsuitable for the task. As a result of the flourishing wheat trade corn exchanges were being built in towns and cities throughout the country, and in 1828 a consortium of local businessmen put together a plan to build a corn exchange in Bishop’s Stortford. The site chosen was that of the King’s Head Inn in the market place.

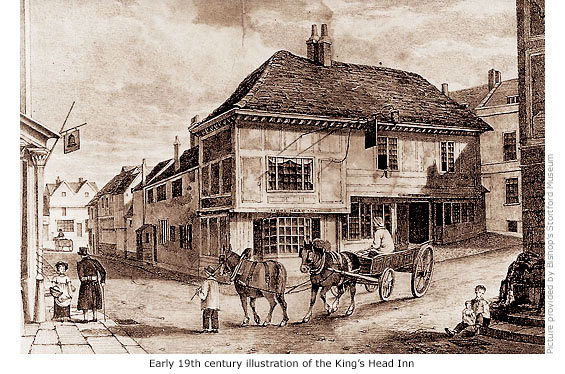

Built in 1680 the King’s Head sign portrayed Henry VIII, but an earlier sign, depicting a bunch of grapes, indicate it was first a tavern. Its elevation to ‘inn’ status was due to the growth in stagecoach travel in the 18th century, but as more and more stagecoaches journeying between London and East Anglia began to avoid the busy town centre in favour of the Hockerill bypass (See Guide 12), the King’s Head’s fortunes declined. It later gained a reputation for being a rowdy house and when the petty sessions or ‘courts’, often held there, moved to the Crown Inn at Hockerill its days were numbered. In 1828 the landlord, George Perry, had little hesitation in accepting the £3,150 offered by the Corn Exchange Company. SEE DETAILS BELOW

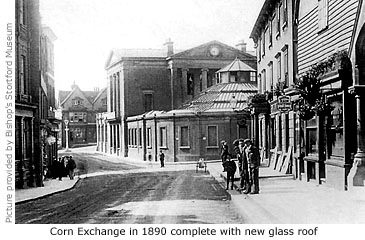

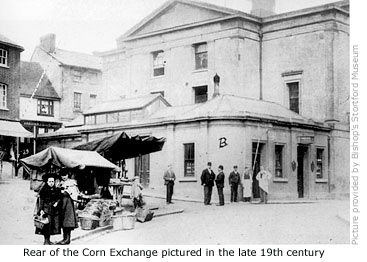

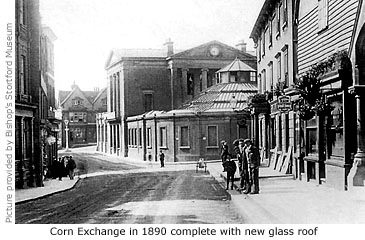

Designed in the neo-classical style by Lewis Vulliamy (See Thorley Guide - Thorley Church), and built in 1928, the Corn Exchange despite much alteration is still one of the few 19th century buildings in Bishop’s Stortford of real architectural merit. It is the oldest corn exchange in Hertfordshire and by far the most distinguished. There is even a suggestion that it inspired the design of St Albans Town Hall in 1832. Designed in the neo-classical style by Lewis Vulliamy (See Thorley Guide - Thorley Church), and built in 1928, the Corn Exchange despite much alteration is still one of the few 19th century buildings in Bishop’s Stortford of real architectural merit. It is the oldest corn exchange in Hertfordshire and by far the most distinguished. There is even a suggestion that it inspired the design of St Albans Town Hall in 1832.

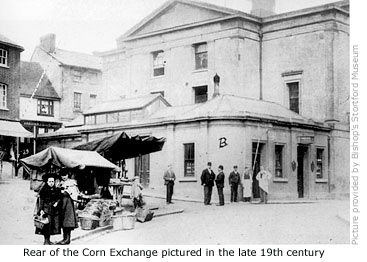

Four giant Ionic columns and pediments support the portico facing North Street, with two similar columns in place on the eastern side above the building’s Market Square entrance. Above the original entrance to the trading floor (currently occupied by a restaurant and a hairdressers), stood a statue of *Ceres the Greek goddess of the earth and, especially, grain. She, along with the building’s turrets and other embellishments was later removed and replaced by a large circular glass roof, giving the 65 dealers who worked here added light by which to judge the quality of grain being purchased and sold. Although called a Corn Exchange, the word ‘corn’ is a generic term for all cereal grain.

A single-storey addition to the rear of the building at the turn of the 20th century housed a barber’s shop and the Capital and Counties Bank then, later, Lloyds Bank before it moved to 20 North Street in the early 1970s.

Although the Corn Exchange was built for the trading of grain, it has since served a variety of purposes. In the 1800s it offered public meeting rooms holding up to 500 people, a library, club, literary society, and facilities to put on plays. The Guardians of the Union Workhouse, who held their first meetings at the George Inn, later moved to the Corn Exchange before building their own headquarters at Hockerill Street (See Guide 8 – Hockerill Street). During restoration of St Michael’s Church in 1868 the exchange was temporarily used for vestry meetings and as the parish church, and during the Second World War (1939–1945) it was used as a synagogue by Jewish refugees from London. Bishop’s Stortford’s Working Men’s Club was founded here in 1873, as was the Conservative Club in 1883. It also acted as a courthouse in the late 1800s.

When the Corn Exchange finally ceased trading in 1959, Hertfordshire County Council bought the premises in order to control development of the site. Willful neglect soon ensured it fell into disrepair and in 1967 the same council proposed to demolish the building as part of the town improvement scheme. Local feelings ran high at this suggestion, the proposal so strongly opposed by the Civic Society and Local History Society that a ministerial decision was made in 1971 to save it. After the reprieve the exchange was sold to a developer who, in 1972, removed the glass roof and restored and converted the building for use as shops and offices. MORE PICTURES

*Ceres (Greek name Demeter) was the sister of Zeus and mother of Persephone. Her name includes the Greek word for 'mother' and an ancient word that probably means 'barley'. She was responsible for the growth of all plants and crops, more especially wheat, and taught humans how to grow plant seeds. The Greeks held a festival each autumn in honour of Ceres, at which only women could take part in and its rituals were kept secret from men. It was intended to bring success to the growing of seed.

*CORN LAWS:

As a result of British farmers growing so much wheat after the Napoleonic Wars, the high price of domestic corn fell far below the stipulated £4 per quarter level that governed duty on imported grain. To placate its supporters the Tory government revised the Corn Laws in 1828 by introducing a sliding scale. This allowed wheat to be imported duty-free when the domestic price rose to 73 shillings (£3.65p) per quarter. The more the price of domestic grain fell below that figure, the higher the duty became. It was, however, a pointless exercise and did nothing to help poor people, manufacturers, or the economy.

In the 1830s the price of wheat fell as low as 35 shillings (£1.75p) per quarter, and in 1842 a further Corn Law raised the domestic rate to 66 shillings (£3.30p) per quarter. But by now everybody, apart from wealthy farmers and landowners, wanted the Corn Laws abolished. The government, in order to keep its supporters happy, had all but ruined the country's economy and the influential factory owners were losing their patience. Abnormally high wheat prices meant high food prices and high wages. Abolition of the Corn Laws would bring low wheat prices and mean they could pay lower wages. They also believed that if Britain imported more wheat, then foriegn countries would buy more goods made in their factories.

Action to try and persuade the government to abolish the Corn Laws was finally taken in 1838 when a group of businessmen formed the Anti-Corn Law League. But despite a seven-year fight, the Tory Party remained loyal to its supporters who were totally opposed to the repeal of the Corn Laws.

The turning point came in 1845 when disease totally destroyed Ireland's potato crop. Unable to grow wheat because the land wasn't fertile enough, Ireland's farmers grew mostly potatoes. Just as bread was the staple diet of the poor in England and Wales, the poor of Ireland ate potatoes. As a result of the famine, one million people died and another million emigrated, mostly to America.

Help for the starving people of Ireland came from the Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel, who decided to repeal the Corn Laws so that wheat could be sent there. His own party were totally opposed to the idea but Peel won the vote with the aid of the opposition who were in favour. The repeal of the Corn Laws caused a major split in the Tory party. Peel resigned and many of those those who had supported the repeal left the Tory Party to join the Whigs (later called the Liberals). In the event, the repeal of the Corn laws had hardly any effect on the price of wheat.

|

|

This is a summary of a document listing various wills and transactions, detailing ownership, land and buildings of the once freehold estate on which the Corn Exchange now stands.

The very first date on the document, 23 September 1686, concerns the will of one Thomas Ashby the elder, of Albury, whose occupation is recorded as ‘Gentleman’. It reads thus:

‘I give and bequeath unto my son, John Ashby, and to his Heirs forever, when he shall have attained his full age of two and twenty years, all that my capital Messuage or Inn, called the King’s Head in Bishop’s Stortford in the county of Hertford, with all and every the Shops, Stalls, Standings, void Grounds, Entrys, Passages, lying next to theFish Market, or any other shops belonging to the King’s Head; and also one other Tenement formerly John Cotter’s, now in the occupation of John Dorrington; and also the Yard and garden formerly called the Cock-pit Yard, and now used for a Bowling Green, with all and singular their and every of their Appurtenances to the said Messuage, Inn, and Tenement, Cock-pit Yard and Bowling Green, and all other of the premises last mentioned, with other Appurtenances unto my said son John Ashby, and his Heirs for ever when he shall attain to his full age of two and twenty years, which said Messuage, Tenement, Inn, and all other of he Premises herein last before mentioned, now are or were in the several Tenures or Occupations of John Perring, Edward Wood, Game Crouch, Janie Jordan, John Dorrington and several others’.

Reading through the legal jargon of the time, John Ashby left to his son, when he reached the age of twenty-two, the King’s Head inn and all other buildings, shops, stalls or standings pertaining to the estate alongside the Fish Market. Also included was one other building in which John Dorrington resided, and a yard and garden formerly called Cock-pit Yard, which at that time was used as a bowling green. (Where this was exactly isn't known, but for obvious reasons it seems unlikely to have been in the vicinity of the market place.)

The will was proved 6 May 1687, and on 7 November 1706 his son, John Ashby, bequeathed all of the same properties mentioned above to his cousin, John Mitchell. At this time the King’s Head was in the tenure of one Joseph Kinsey; the house where John Dorrington lived also included a shop; and there is mention of another house in which Andrew Brand lived. Reference was also made to the ‘Piece of Ground called the Bowling green, lying in Stortford’.

The will goes on to stipulate that the bequeathed estate was on condition that John Mitchell, his Heirs, Executors, Administrators or Assigns, should pay his sister Sarah Mitchell, the sum of £100 when she reached the age of eighteen, or at the day of her marriage – whichever came sooner. If the £100 wasn’t paid at either of the stipulated times in her life, then 'it would be lawful for her or her Assigns to enter any of the properties bequeathed in the will, and receive, have, and take the rents, issues and profits thereof until the said sum, together with any charges incurred, be fully paid and satisfied'.

The estate then passed by will made on 4 April 1761 to John Mitchell's son, Thomas, who in his will dated 14 August 1769, then of Rickling Hall, Essex, and described as ‘gentleman’, bequeathed all the Stortford properties to his housekeeper Elizabeth Feast.

She held the King's Head and related properties for a time but in November 1791 sold it to John Rawlins of Bishop's Stortford, described as an innkeeper, for £1,000. Rawlins died in September 1792 leaving the property to his wife in trust.

'That she may if necessary sell and dispose of the same for the purpose of paying any monies that may have been borrowed to complete the purchase thereof and likewise the legacies bequeathed to my daughter Susanna and sons John and Henry.'

At her death, Elizabeth bequeathed the property to her son John upon trust, 'to pay and divide the same together with money arising from the sale of her real estate unto and amongst her four children, Ann the wife of William Stacey; Susan the wife of George Perry and John and Henry Rawlins’. The four children mentioned here are Ann, Susan (Susanna), George and John. The fourth child, Ann, didn't appear in her husband's will so was presumably from a previous marriage. The will was proved 22 December 1824.

On 21 January 1828 the property was sold by William Stacey (in full agreement with the other members of the family) to George Perry, innkeeper of Bishop’s Stortford, and in the same year purchased for £3,150 for the purpose of erecting a Corn Exchange on the site.

The sale included 'the King’s Head, with the ground and soil thereof together with all and singular the Yards, Stables, Haylofts, Edifices and Buildings belonging to the premises and also all those Tenements, Shops, Sheds, Stables lying round and adjoining the inn.

Before the sale these various properties were in the tenure or occupation of: John Perry; Alexander Ramsey, William Christy, ____ Woolman, William Wood, ______Markwell and William Lamb. At the time of sale some of the same properties were in the occupations of the Widow Markell, James Franklin, Thomas Forsuch, William Fuller and John Barber.

Indentures made on 31 May 1828 record that George Perry sold the King’s Head inn and all respective properties of the estate to a consortium of fifty-nine people. Of these, fifty-eight were to pay one-sixtieth of the purchase price, and Sir George Duckett was to pay two-sixtieths. This works out approximately £53. 8s. 0d. (£53.40p) each, with George Duckett paying £106. 16s. 0d. (£106.80p)

The Corn Exchange was also to be vested in Trust, made up of members of the consortium. Part of the Indenture states: that if any trustee of the present time or of a later date should die, discharge themselves, decline, or become incapable to act as a trustee, then the remaining trustees could appoint any person or number of persons they so wished to take their place or places as a trustee. This practice could continue until the number of trustees was reduced to just three.

The charge made by the solicitor for handling the conveyance was ten shillings (50p) to the consortium and five shillings (25p) to George Perry.

A Schedule attached to the document lists the fifty-nine names that collectively bought the estate in order that a Corn Exchange be built on the site. CLICK HERE FOR A FULL LIST

|

|

|

|

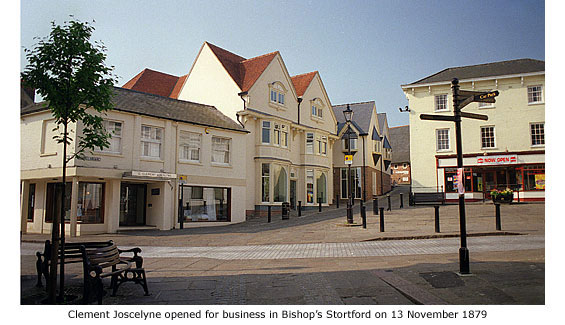

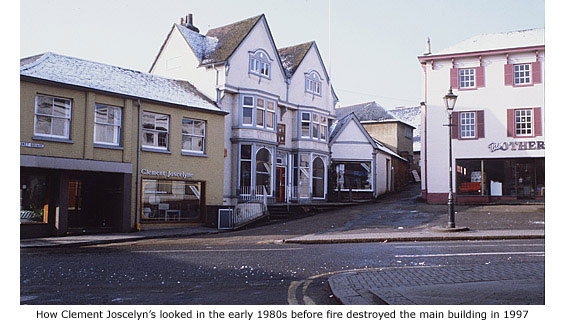

Clement Joscelyne |

|

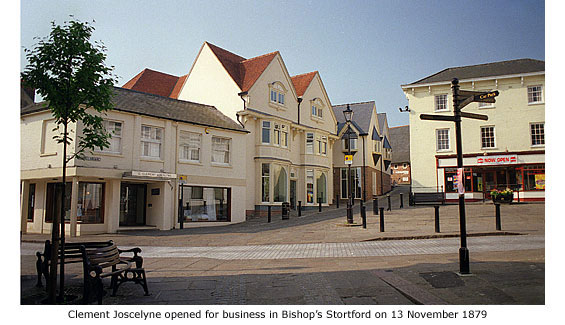

The name Joscelyne has been associated with Bishop's Stortford ever since 1879, when Clement Joscelyne cycled here from Braintree, Essex, to find premises in which to start a furniture shop. For sale he found No 16 Market Square, a 16th century premises occupied by George Sapsford, butcher and slaughterer. The property was described as 'two dwelling houses with front shops, large enclosed yard, slaughterhouse, cattle pound, stable and a cottage with blacksmith's shop'.

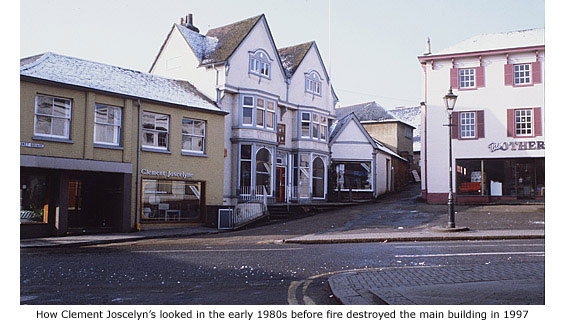

After buying the premises for £1,100 and setting up home above the shop with his wife, Fanny Crittall, he then began to transform the double-fronted building by adding a new front and ornate bay windows. When the shop finally opened for business on 13 November 1879 its only entrance was a door between the bay windows, but the main entrance today is in the smaller building adjoining it – previously the Plume of Feathers public house. Church records first mention this inn in 1679, and it traded continually until 1960 when Joscelyne’s took possession to enlarge their store. Alterations made to the outer wall included large shop windows and the creation of a narrow colonnade along the pavement in Potter Street.

Tragically, the building in which the store began accidentally caught fire in May 1997, the resulting damage so great that it was decided to demolish the remains and replace it with an exact replica. And that is what you see today. Using modern construction methods, skilled workers recreated the gabled exterior of the 16th century building to look exactly as it did before the fire. The entire rebuild, inside and out, was swift and the new store reopened for business in December 1998.

To all who shopped at Clement Joscelyne's in the early years of the new millennium, it appeared that all was well. But in September 2009 came news that a large part of the store had been bought by Hertford-based brewers McMullen for development as part of its Baroosh bar chain. After 130 years, only the front part of Joscelyne's in the town, that facing Potter Street and previously the Feathers public house, would remain as a gift department. The bulk of Joscelyne's business was to move to a new flagship premises in Fitzroy Street, Cambridge. Clement Joscelyne was succeeded by his son Charles in 1911, and is currently run by Raymond Joscelyne. The family business has several branches across the South East and London.

McMullen developed the rear half of the building into a bar restaurant and the upper floors into self-contained flats and staff accommodation. Baroosh opened 30 October 2011. MORE PICTURES

|

|

[ BACK TO TOP ] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In 1821 Bishop’s Stortford’s population of 3,358 were suffering the effects of the *Corn Laws like everybody else, more so the working classes who struggled to feed their families. Of more pressing concern to local farmers and landowners, however, was that Wheat Hill (now High Street), where grain had been traded since the Middle Ages, was now proving unsuitable for the task. As a result of the flourishing wheat trade corn exchanges were being built in towns and cities throughout the country, and in 1828 a consortium of local businessmen put together a plan to build a corn exchange in Bishop’s Stortford. The site chosen was that of the King’s Head Inn in the market place.

In 1821 Bishop’s Stortford’s population of 3,358 were suffering the effects of the *Corn Laws like everybody else, more so the working classes who struggled to feed their families. Of more pressing concern to local farmers and landowners, however, was that Wheat Hill (now High Street), where grain had been traded since the Middle Ages, was now proving unsuitable for the task. As a result of the flourishing wheat trade corn exchanges were being built in towns and cities throughout the country, and in 1828 a consortium of local businessmen put together a plan to build a corn exchange in Bishop’s Stortford. The site chosen was that of the King’s Head Inn in the market place. Designed in the neo-classical style by Lewis Vulliamy (See Thorley Guide - Thorley Church), and built in 1928, the Corn Exchange despite much alteration is still one of the few 19th century buildings in Bishop’s Stortford of real architectural merit. It is the oldest corn exchange in Hertfordshire and by far the most distinguished. There is even a suggestion that it inspired the design of St Albans Town Hall in 1832.

Designed in the neo-classical style by Lewis Vulliamy (See Thorley Guide - Thorley Church), and built in 1928, the Corn Exchange despite much alteration is still one of the few 19th century buildings in Bishop’s Stortford of real architectural merit. It is the oldest corn exchange in Hertfordshire and by far the most distinguished. There is even a suggestion that it inspired the design of St Albans Town Hall in 1832.