|

Church records first mention New Town in the 16th century, the name perhaps a little exaggerated at that time as it probably applied to only a few scattered houses south of the town centre. No buildings survive from that period but a few small developments built in the early 19th century do still stand in Newtown Road and Apton Road.

Only after the arrival of the railway in 1842 did large-scale development of the area take place, starting with Victorian terraces that were mostly rented by railway workers. But for anybody wishing to buy a new house here there were certainly inducements to do so, though it’s unlikely the offer made by the Great Eastern Railway Company of a seven year reduced rate first class ticket, would ever be considered by today’s property developers.

The Conservative Land Society advertised further developments in the Cemetery Road area in 1864, and by the late 1800s and early 1900s New Town finally lived up to its name. Many of the later houses were built by local builder Frederick Cannon, who up until 1933 constructed each and every one with hand-made bricks.

|

|

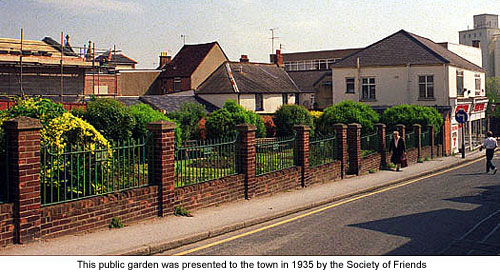

A small public garden near to the bottom of this steep hill is planted mainly with shrubs and roses and bordered, on the roadside, by a wall topped with iron railings. The entrance gate is always open and seats are available to sit and enjoy this small oasis in the heart of the busy town.

In the early 20th century, when this ground was encompassed by a high brick wall, a regular event held here was the singing of hymns by groups of children for the benefit of a public audience. It was organised by James Dorrington Day, owner of a building firm in South Street (See Guide 13), and any money given by appreciative audiences helped pay for local children to go on summer outings to the seaside.

The small civic monument that stands directly opposite the entrance gate was originally commissioned by the Bishop’s Stortford branch of the British Women’s Temperance Association to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897. Made of pink marbel, and funded by public contributions, the monument stood in Northgate End near to the cattle market until the mid 1900s, when a change in attitude towards the past deemed it no longer relevant and consigned it to the workmen’s yard at New Cemetery. Fortunately, attitudes change and in 2003 it was it decided the monument should once again be exhibited. The small civic monument that stands directly opposite the entrance gate was originally commissioned by the Bishop’s Stortford branch of the British Women’s Temperance Association to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897. Made of pink marbel, and funded by public contributions, the monument stood in Northgate End near to the cattle market until the mid 1900s, when a change in attitude towards the past deemed it no longer relevant and consigned it to the workmen’s yard at New Cemetery. Fortunately, attitudes change and in 2003 it was it decided the monument should once again be exhibited.

A small plaque on the wall behind the monument reads: This garden was presented to the town of Bishop’s Stortford by the Society of Friends on 3rd October 1935.

The Society of Friends, otherwise known as Quakers, is a religious body started by George Fox (1624–1691). Born in Leicestershire to puritan parents he first began to preach his beliefs in 1647, but his opinion offended the established Church and in 1650 he was convicted of blasphemy. At his conviction he told the presiding judge to tremble at the word of the Lord, after which the judge referred to Fox and his followers as ‘Quakers’.

The first Quaker community was formed in northern England in 1652 and religious meetings quickly spread throughout the country. Meetings were always well attended, but Quakers were unpopular with both the ecclesiastical and civil authorities because of their refusal to attend church or have their children baptised. This often resulted in riots, with many Quakers prosecuted and jailed or sent overseas for their beliefs.

One early convert, and a powerful protector, was William Penn (1644–1718), the son of Admiral Penn who had some influence with the last two Stuart kings. He journied to America in 1681 to found Pennsylvania Colony as a religious and political haven for Quakers, the proprietorship of which he secured from Charles II in lieu of a loan his father had earlier advanced to the Crown.

|

|

First mention of Quakers in Hertfordshire was in 1656, and monthly meetings at Sawbridgeworth were well established by 1659 attracting people from Cheshunt, Hertford and Ware. Quakers first emerged in Bishop’s Stortford in 1678, although the first licenced meeting house, built close to this site in Newtown Road, wasn’t registered until 1691. A new meeting house built near to this site in 1709 replaced it.

When William Penn made a return trip to America in 1684, he was joined by a Quaker convert named Dr Robert Dimsdale. He was originally from Hertford but on his return to England chose to settle in Bishop’s Stortford. The family seems to have been unique at producing doctors; the town of Hertford at that time had at least one Dr Dimsdale and at other times as many as three. Robert’s brother, John, carried on their father’s practice in Hertford, and when the Hertford family line of Dimsdales eventually died out, Thomas Dimsdale, grandson of Robert, inherited his uncle’s property there.

A series of Dr Dimsdales also served Bishop’s Stortford throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, and it was one of these who retrieved and kept safe part of the Grammar school's large collection of library books when it was pulled down in 1770 (See Guide 3). The Dimsdale family had been Quakers since the start and became leading figures in the Bishop’s Stortford Meeting House shortly after it was founded. William Dimsdale, surgeon, was one of the trustees. A series of Dr Dimsdales also served Bishop’s Stortford throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, and it was one of these who retrieved and kept safe part of the Grammar school's large collection of library books when it was pulled down in 1770 (See Guide 3). The Dimsdale family had been Quakers since the start and became leading figures in the Bishop’s Stortford Meeting House shortly after it was founded. William Dimsdale, surgeon, was one of the trustees.

However, by 1722, membership here was somewhat lacking in numbers and in 1748 the meeting house was discontinued. Local Quakers then joined the more numerous congregations at Hertford, Thaxted and Stansted, but by the early 19th century these meetings also became less frequent and were finally discontinued in 1850. There was a brief resurgence in Bishop’s Stortford between 1963 and 1967 but the meetings moved to Stansted soon after.

Dr Thomas Dimsdale (1712–1800), holder of a medical degree from Aberdeen in Scotland, was destined to become the most famous member of the entire family, for it was he who was one of the early pioneers of inoculation as a method of controlling smallpox – the scourge of the 18th century.

Smallpox was considered to be an exceptionally serious disease, so much so that in Bishop’s Stortford an apothecary was appointed to provide all the medicines necessary for inmates of the workhouse, except in the case of smallpox. All persons infected by it were isolated in the ‘Pest House’ that stood at the top of Maze Green Road (See Guide 5). A particularly tragic case of the disease is recorded in a monument in St Michael’s church, which details the deaths of Edward Maplesden's seven children (See Guide 4).

The idea of inoculation had first been made popular by the efforts of Lady Mary Wortley Montague (1689–1762), who witnessed the method used in Turkey. Thomas Dimsdale’s method was to inoculate a healthy patient using matter from someone who already had the disease. The patient would then suffer an attack of smallpox, but due to adequate preparations was able to recover quickly and so become immune to further infection. He also advocated a strict regime of diet, fresh air and gentle exercise both before and after inoculation. It was naturally a far more hazardous undertaking than vaccination as we know it today, which follows the Edward Jenner (1749–1823) method first used in 1796. His initial experiments involved inoculation with the related cow-pox virus to build immunity against the deadly smallpox virus

In 1767 Dr Dimsdale published a paper on the subject and in October the following year was invited to visit Russia to inoculate the Empress Catherine. At that time, outbreaks of smallpox were devastating populations worldwide so to safeguard her people, and set an example, she volunteered to be inoculated.

Had anything gone wrong, it is said that a team of horses were kept in readiness to whisk the doctor away should the Russians seek vengeance against him. Thankfully all went well, and the grateful Catherine showered the doctor with gifts of diamonds and furs, plus £12,000 and a life annuity of £500. He was also bestowed with a hereditary barony of the Russian Empire, which is still held by the family. She later bought houses in Moscow and St Petersburg, which Dr Dimsdale used as vaccination hospitals.

Dr Thomas Dimsdale never actually practised in Bishop’s Stortford, instead he kept the Hertford practice going. He was MP for Hertford in 1780 and 1784, and married as his third wife his cousin Elizabeth, great grand-daughter of Robert Dimsdale. When Thomas died in 1800, aged 88, his request was to be buried in the Friends’ burial ground at Bishop’s Stortford along with other members of his family. When his wife died, twelve years later, she was buried alongside him.

This small public garden is Bishop's Stortford Quaker burial ground. A large memorial stone mounted on the far wall, just to the left of the small plaque, is inscribed: In these grounds are buried under; and goes on to list seven members of the Dimsdale family and five other Quakers, all of whom died between 1779 and 1823.

In 1984 the laying of a gas main in Newtown Road unearthed a lead coffin containing the remains of a skeleton, but when it proved to be unidentifiable was re-interred in the Quaker burial ground.

|

The small civic monument that stands directly opposite the entrance gate was originally commissioned by the Bishop’s Stortford branch of the British Women’s Temperance Association to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897. Made of pink marbel, and funded by public contributions, the monument stood in Northgate End near to the cattle market until the mid 1900s, when a change in attitude towards the past deemed it no longer relevant and consigned it to the workmen’s yard at New Cemetery. Fortunately, attitudes change and in 2003 it was it decided the monument should once again be exhibited.

The small civic monument that stands directly opposite the entrance gate was originally commissioned by the Bishop’s Stortford branch of the British Women’s Temperance Association to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897. Made of pink marbel, and funded by public contributions, the monument stood in Northgate End near to the cattle market until the mid 1900s, when a change in attitude towards the past deemed it no longer relevant and consigned it to the workmen’s yard at New Cemetery. Fortunately, attitudes change and in 2003 it was it decided the monument should once again be exhibited. A series of Dr Dimsdales also served Bishop’s Stortford throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, and it was one of these who retrieved and kept safe part of the Grammar school's large collection of library books when it was pulled down in 1770 (See Guide 3). The Dimsdale family had been Quakers since the start and became leading figures in the Bishop’s Stortford Meeting House shortly after it was founded. William Dimsdale, surgeon, was one of the trustees.

A series of Dr Dimsdales also served Bishop’s Stortford throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, and it was one of these who retrieved and kept safe part of the Grammar school's large collection of library books when it was pulled down in 1770 (See Guide 3). The Dimsdale family had been Quakers since the start and became leading figures in the Bishop’s Stortford Meeting House shortly after it was founded. William Dimsdale, surgeon, was one of the trustees.