|

By 1860 most of the rail network was in place, leaving only the gaps between main line stations to be filled. Central and West Essex, a predominantly rural area, had been largely ignored during the initial development because it wasn’t considered a viable proposition.

This view changed in the early 1850s when the Bury St Edmunds Railway Company proposed to run a line between Bury St Edmunds and London, via towns in West Essex. This was to include the ancient and important town of Dunmow that had no rail link to anywhere.

Eastern Counties Railway (ECR), fearing their monopoly in East Anglia would be threatened by Midland Railways and others linking up with this new line, put up strong opposition to the plan and in 1859 managed to cajole the Epping Railway into obtaining an Act of Parliament to extend their line from Chipping Ongar to Dunmow. Even so, there was still a financial risk involved with the project and there was no certainty they could beat the Bury St Edmunds link into London.

Fortune was on their side though. That same year an unexpected proposal was submitted to ECR by a group of Hertfordshire businessmen, including maltsters, millers and coal merchants from Bishop’s Stortford and Sawbridgeworth, who were anxious to obtain easy transport for malt and barley from towns and villages in West Essex.

Their proposal was for a railway line, 18 miles long, linking the towns of Bishop’s Stortford, Dunmow and Braintree. The directors of ECR knew that if Dunmow could be linked to a main line it would allow them to fend off opposing railway companies from entering East Anglia, thereby safeguarding their monopoly of the area.

They readily agreed to the proposal, offering to have the route surveyed and donating £40,000 to help with construction. The application to parliament did encounter some opposition though, and went before the House of Commons Select Committee. But eventually, by Act of Incorporation in July 1861, permission was given for the branch line to go ahead. As a consequence, financial backing for the proposed Bury St Edmunds to London line dried up almost immediately and the project was abandoned in December that same year.

In 1862 ECR was amalgamated with the Great Eastern Railway (GER) but directors were adamant they would continue with the branch line. Various interested parties subscribed money for construction, although the towns of Bishop’s Stortford and Braintree considered the project something of a ‘white elephant’ and their subscription fell far short of expectation.

Despite poor local backing and the shortfall in subscriptions, GER decided to fully finance the line themselves and absorb all of the shares of the local company. By doing so it meant they would ultimately buy the railway outright and thereby prevent any independent railway from linking London with East Anglia, especially via Dunmow.

There were still many complications to overcome, including certain land purchases, but eventually it all came together and Dunmow was chosen (being the half-way point between Bishop’s Stortford and Braintree) to be the place of ceremony where the first turf would be cut. For such an event in the town’s history, the 24 February 1864 was declared a local public holiday, with celebrations lasting the entire day and well into the night.

Contractors began work the following morning but in the coming months construction of the route didn’t prove to be quite as easy as first thought – its initial cost being seriously underestimated. By 1866, however, the extra money had been raised and all major earthworks on the line completed.

Further setbacks came after a Board of Trade inspection called for several improvements to the route, and on a subsequent inspection to sections of the track and station platforms. Virtually the entire length of the branch line’s 18 mile route was single track, except at Dunmow and one or two other stations where dual track allowed trains to pass each other. The line was finally opened for passenger use on 22 February 1869.

With hindsight, it is now apparent that the branch line was never going to succeed as a profit making passenger service. Throughout the 19th century, poverty and a lack of opportunities was driving people away from the Home Counties to the more prosperous industrial area of London and its suburbs. The arrival of the railway in the 1840s only served to accelerate this movement, offering both rapid and inexpensive access to the capital and leaving rural areas with a dwindling population. Added to this was the fact that the three towns linked by the line had their own industries, meaning there was very little need for workers to travel.

The branch line’s saviour came in the 1880s. The sudden demand for agricultural produce in London, combined with new industries that were starting up in Braintree, both required a freight service and it was this that was to provide important revenue for the railway. Freight traffic continued to grow, especially at the Braintree end of the line, but by the end of the 19th century passenger traffic to Bishop’s Stortford remained light.

One important person who regularly used the line at that time was the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII), who made frequent visits to see the Earl and Countess of Warwick at their home, Easton Lodge near Dunmow. In order that her home should be more accessible to such important guests, the countess negotiated with GER to provide a station nearby, and in 1895 a small halt called Easton Lodge was constructed at a cost of £140. As per the agreement, the countess agreed to pay GER £52 annually for 10 years for the upkeep of the station, and also agreed it should be made available for public use. One important person who regularly used the line at that time was the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII), who made frequent visits to see the Earl and Countess of Warwick at their home, Easton Lodge near Dunmow. In order that her home should be more accessible to such important guests, the countess negotiated with GER to provide a station nearby, and in 1895 a small halt called Easton Lodge was constructed at a cost of £140. As per the agreement, the countess agreed to pay GER £52 annually for 10 years for the upkeep of the station, and also agreed it should be made available for public use.

Over the years various efforts were made by Eastern Counties Railway to increase passenger traffic, including in 1910 the building of Hockerill Halt, a small, unmanned stopping point near to Bishop’s Stortford’s golf club situated close to the Dunmow Road. Trains would only stop here by request (hence the name, halt) but it was little used by patrons of the club and the service was eventually suspended (See Guide 10).

At the war's end in 1918, Parliament decided that the inefficiencies of the 100-plus small railway companies operating throughout the country should be merged into four Group Companies: the London and North Eastern (LNER), London Midland and Scottish (LMS), Southern (SR), and Great Western (GWR).

When GER finally amalgamated with the London & North Eastern Railway (LNER) on 1 January 1923, the new company made every effort to increase passenger traffic on the branch line by doubling the initial three passenger trains a day running in each direction, to six. But all to no avail. It was still the carriage of freight that supplied the revenue and there was an abundance of it, including barley, wheat, hay, straw, milk, vegetables, coal and livestock. Hunting horses were also transported between meetings in horseboxes attached to passenger trains.

During the Second World War the line was used to transport thousands of tons of rubble for the construction of Saling airfield, 5 miles from Braintree and, later, when it became operational, massive loads of bombs were carried to the same destination under cover of darkness.

The United States Air Force bases at Stansted and Easton Lodge were also regularly supplied with armaments and stores arriving via Bishop’s Stortford and Takeley station. The Germans obviously knew of this and trains were often machine gunned by the marauding Luftwaffe. Attempts were also made to bomb these ammunition trains and on one occasion a train was attacked while climbing the gradient towards Hockerill. A stick of bombs missed the train, but one landed in Dunmow Road near to the railway bridge and another fell on Hockerill Training College, killing three young students (See Guide 10).

After the invasion of Europe in June 1944 the line was used by ambulance trains to bring back wounded soldiers – via the port of Harwich – to the military hospital at Haymeads Lane. The injured were off-loaded at Hockerill Halt.

By the end of the war (1945), the railways were in a very poor state and the government of the day, as part of their post-war policy, elected to nationalise the industry. On 1 January 1948 the former ‘Big Four’ companies were amalgamated into one enterprise known as British Railways – later shortened to British Rail – and divided into six regions.

But the times they were a changing. The public’s use of motor cars and increased competition from bus transport meant the passenger service between Bishop’s Stortford and Braintree ran virtually empty and, inevitably, closure of the line for passenger traffic was announced. Despite public protests, the last train to run between the two towns was on 1 March 1952.

That evening a large number of people assembled at Braintree to make the final return trip to Bishop’s Stortford, and at 18.38 the last train pulled out of the station – a black wreath placed on its boiler by the Braintree stationmaster. Four coaches instead of the usual two carried ten times the number of people who normally travelled the line, and with many others picked up from stations along the way the train eventually arrived in Bishop’s Stortford five minutes late. Forty-five minutes later, at 20.15, the train left the town for the very last time to the accompaniment of whistles from locomotives standing in the goods yard and exploding fog signals placed on the line by railway workers.

Despite the loss of the passenger service after 83 years the line was kept open for freight traffic, which was still an important source of revenue. A special freight service served Hockerill until 1960 (See Guide 10), and from March 1962 the line was used to carry bananas to the newly built Geest factory at Easton Lodge. Up to 300 tons of unripe fruit was transported to the factory every week where it was stored to ripen.

The Beeching Report of 1963, responsible for the closure of most branch line services throughout the country, recorded that Bishop’s Stortford was dealing with over 25,000 tons of freight traffic annually. This fact alone probably saved it from Dr Richard Beeching’s infamous axe.

But by 1968 more and more freight was being transported by road, making the branch line uneconomical to keep open. By the end of 1971 all freight traffic had ceased, and on 27 July 1972 a final enthusiasts trip ran from Bishop’s Stortford to Easton Lodge and back. And that was it!

By the autumn of that year most of the track had been taken up, apart from the last mile out of Bishop’s Stortford. British Rail were considering the possible role this section of line might play in carrying additional traffic to a growing Stansted Airport, but proposals came to nothing and in 1974 the remaining track was removed.

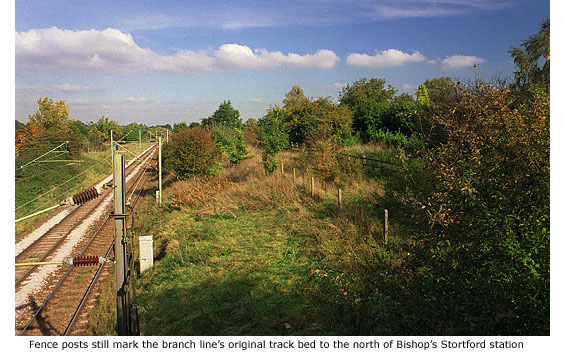

The only trace to be found now of the branch line’s former route is just north of Bishop’s Stortford station where the track left the main line heading east. Looking north from the *footbridge that crosses the railway on the Meads, the track bed can be seen on the eastern embankment within a fenced-off area running parallel to the main line. From here the line then curved in a steep climb towards another (man-made) embankment that took it onto Collins Cross bridge and across Stansted Road (See Guide 10).

MORE PICTURES

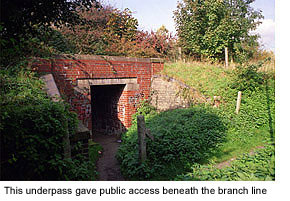

*Access to the Meads footbridge from the east is via a footpath that leads from Kingsbridge Road to a small, brick-built underpass, originally constructed to allow pedestrians to walk beneath the branch line.

|