|

The mostly early 19th century houses that now line this wide and picturesque road were originally built as homes for wealthy and professional local people. It was their affluent disposition that allowed them to live here away from the noise and noxious smells of the town's market. Today the market place is no longer noisy, nor are their any bad smells, but Windhill is still a sort after address.

The name 'Wyndhell' first appeared in documents of the 13th and 14th century and is likely to have been called as such because of the hill's lofty and exposed position above the town. At that time it was probably void of all buildings except for the church but by the Middle Ages, combined with the churchyard (until the 16th century), it was the regular venue of fairs and church fund raising events – chiefly church ales and bonfire parties.

It was also the stage for Bishop’s Stortford’s Ancient Dragon, a life-like construction made of painted canvas stretched over hoops and operated by men from within. Regularly used for plays and processions it was also rented out to local towns and villages. One play always extremely popular with townspeople was based on the story of St Michael and the dragon, but after Edwardian Reforms (1549) banned such frivolities the dragon was sold in 1550 and never seen again.

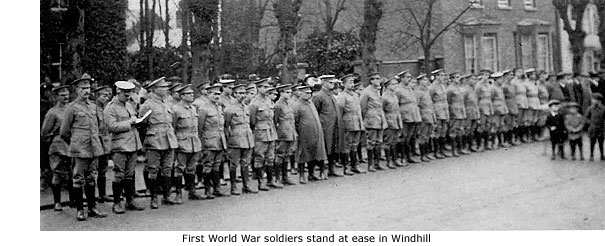

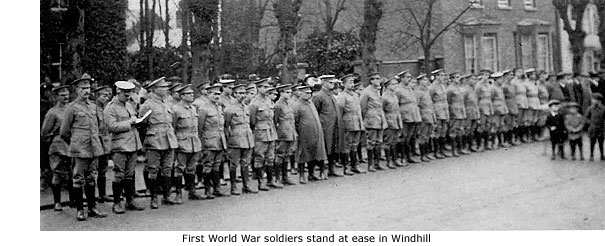

It is thought that three public houses – the Coach and Horses, the White Hart, and the Bell – also once traded in Windhill, but apart from the Bell (see Guide 3) little more than their names are known. In the mid 19th century the 1st Herts Light Horse Regiment trained in a house here, and during the First World War the local Home Guard regularly lined up in the road to await their C.O.’s inspection.

It is also recorded that between November 1914 and March 1915, thousands of men of the Leicestershire Regiment, including the 1st 5th North Midland Territorial Force, were billeted in and around Bishop’s Stortford before their onward journey to the battlefields of France. When the soldiers finally left, it is said to have taken more than three hours for them all to march down Windhill towards the Causeway where many of their horses were stabled, and then on to the railway station where they departed for Southampton, via London. There was some concern among town officials that the sewers running beneath Windhill, newly installed at the end of the 19th century, would collapse under the weight of so many marching men but, thankfully, their fears were unfounded.

The following is taken, in part, from The Fifth Leicestershire – A record of the 1st 5th Battalion the Leicestershire Regiment, T.F., During the War, 1914–1919, by J.D. Hills. Based mainly on the Regimental War Diary, this book was first published in 1919 and is now available, free, on the internet, courtesy of The Project Guthenberg.

www.gutenberg.org/files/17369/17369-h/17369-h.htm

The infantry of the 46th (North Midland) Division consisted of the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire, the Lincolnshire and Leicestershire, and the Staffordshire Brigades. The 5th Leicestershire was a County Battalion, organised in eight companies, with headquarters respectively at Ashby-de-la-Zouch, Oakham, Melton Mowbray, Hinckley, Market Harborough, Mountsorrel, Shepshed, and one at Regimental Headquarters at Loughborough. Only at annual training camps did they meet as a battalion.

The Territorial Force left Loughborough for Duffield on 12 August 1914 and there, the following day, were asked to offer their services abroad. It must be remembered that a great many of these volunteers were skilled men in civilian life, who had initially joined the Territorial Army for home service and home defence. A rough estimate by those in command thought that about 70 percent of the men would comply but when the question was put to the men again on 17 August, an estimated 90 percent were willing to extend their services for king and country.

They left Duffield on the 15th of August, and marched to Derby Station where they boarded a train for Luton. As in Loughborough, their billets were schools but when the education branch of the Town Council determined that the future of a nation depended upon the education of her children, the troops moved out on 28 August and entered billets in West Luton. These were in private houses, where usually three to four men were accommodated at various rates. On 2 October a universal rate of 9d a day was fixed for each man. The troops were in Luton just 3 months, training for war. Then at 1 am on Monday 16 November, orders were received to move at 7 am for Ware in Hertfordshire, a distance, by the route set, of 25 to 30 miles. They arrived at 7-20 pm that evening, except for two Companies who were detached as rear guard to the Division. The tail end of the Divisional train lost touch and took the wrong turning, and for this reason the two Companies did not come in till 11-30 pm.

The following extracts tell how the 5th Leicestershire Battalion (about 1,000 men) stayed in Bishop's Stortford for just one week before being billeted in Sawbridgeworth.

Having rested a day at Ware, we marched to Bishops Stortford, where we cannot say we were billeted neither can we use again the word rest, for the town was over-crowded, and queues were formed up to billets; queues composed of all arms of the service, and infantry did not take the front place. Let us say we were "stationed" there one week. The week was enlivened by strange rumour of German air attacks, and large patrols were kept on the watch at night.

On the 26th of November, the time of our life began when the regiment marched into billets at Sawbridgeworth. The town was built for one infantry regiment and no more. The inhabitants were delightful, and we have heard, indirectly, more than once that they were pleased with us. We soon learnt to love the town and all it contained, and we dare not say that our love has grown cold even now. The wedding bells have already rung for the regiment once at Sawbridgeworth, when Lieut. R.C.L. Mould married Miss Barrett, and we do not know that they may not ring again for a similar reason. In Sawbridgeworth, our vigorous adjutant, Captain W.T. Bromfield, was at his best. Everyone was seized and pulled up to the last notch of efficiency, pay books were ready in time, company returns were faultless, deficiency lists complete, saluting was severer than ever, and echos of heel clicks rattled from the windows in the street. Best of all were the drums. Daily at Retreat, Drum Sergt. Skinner would salute the orderly officer, the orderly officer would salute the senior officer, then all the officers would salute all the ladies, the crowd would move slowly away, and wheel traffic was permitted once more in the High Street.

Then came a sudden desire to cross streams, however swollen, and a party rode off to Bishops Stortford to learn the very latest plans. We had just received a set of beautiful mules, well trained for hard work in the transport. As horses were scarce, and the party large, our resourceful adjutant ordered mules. Several mules returned at once, though many went with their riders to the model bridge, and in their intelligent anxiety to get a really close view, went into the water with them.

On another day we did a great march through Harlow, and saluted Sir Evelyn Wood, V.C., who stood at his gate to see us pass.

Football, boxing and concerts, not to mention dancing, filled our spare time, and there was the famous race which ended:--BOB, Major Toller, a, 1., BERLIN, Capt. Bromfield, a, 2. And we are not forgetting that it was at Sawbridgeworth that we ate our first Christmas war dinner. Never was such a feed. The eight companies had each a separate room, and the Commanding officer, Major Martin, and the adjutant made a tour of visits, drinking the health of each company in turn – eight healths, eight drinks, and which of the three stood it best? Some say the second in command shirked.

When, on the 18th of February, the G.O.C. returned from a week's visit to France, and gave us a lecture upon the very latest things, we knew we might go at any time. Actually at noon on the 25th we got the order to entrain at Harlow at midnight, and the next morning we were on Southampton Docks.

We left behind at Sawbridgeworth Captain R.S. Goward, now Lieut. Colonel and T.D., in command of a company which afterwards developed into a battalion called the 3rd 5th Leicestershire. This battalion was a nursery and rest house for officers and men for the 1st Fifth. It existed as a separate unit until the 1st of September, 1916, and during those months successfully initiated all ranks in the ways of the regiment, and kept alive the spirit which has carried us through the Great War.

In World War I, The Leicestershire Regiment raised a total of 22 battalions from its pre-war establishment of two regular, one reserve and four territorial battalions. The regiment was awarded a total of 37 battle honours and three of its soldiers won Victoria Crosses. The regiment lost a total of 336 officers and 6,692 soldiers as casualties during the war.

The following is taken from The Leicester Regiment In World War One – An Outline History and Casualty Figures For Each Battalion, by Iain Kerr.

www.militarybadges.org.uk/mimage/leicww1.htm

The 1/4th Battalion, The Leicestershire Regiment (Territorial Force) was mobilised at Oxford Street, Leicester on 4 Aug 1914 and assigned to the Lincoln and Leicester Brigade in the North Midland Division. It was moved to the Luton area. In Nov 1914 it was moved to Bishops Stortford. On 3 Mar 1915 it embarked for France, landing at Le Havre. On 12 May 1915, the formations were retitled 138th Brigade in 46th (North Midlands) Division. On 21 Jan 1916 it embarked at Marseilles for Egypt but disembarked the next day as the move was cancelled. The battalion ended the war in the same formation on 11 Nov 1918 at Dains du Nord, south-east of Avesnes, France.

The 1/5th Battalion, The Leicestershire Regiment (Territorial Force) was mobilised at the Drill Hall, Loughborough on 4 Aug 1914 and assigned to the Lincoln and Leicester Brigade in the North Midland Division. It was moved to the Luton area. In Nov 1914 it was moved to Bishops Stortford. On 28 Feb 1915 it embarked for France, landing at Le Havre. On 12 May 1915, the formations were retitled 138th Brigade in 46th (North Midlands) Division. On 21 Jan 1916 it embarked at Marseilles for Egypt but disembarked the next day as the move was cancelled. The battalion ended the war in the same formation on 11 Nov 1918 at Dains du Nord, south-east of Avesnes, France.

A *book published in 1996 consists of many letters sent home by a young soldier of the First World War, named Frederick Brian Wade. His unit, King Edward's Horse – a cavalry regiment of the Special Reserve – did most of their training in Hertfordshire, and between March and July 1915 found themselves billeted in Bishop's Stortford. In a letter to his mother he wrote:

'It is now seven o'clock and at eight I take my turn on guard at one of the stables. I'm writing this near a fire in an old inn called the Boar's Head. There are many such old-fashioned inns in this town one in particular is said to be over six hundred years old. Bishops Stortford is situated about thirty miles due north of London and is a miserable little one-horse place with only one picture-palace and with inhabitants with very provincial ideas, who hardly know what is taking place outside their own circle'.

*Peace, War and Afterwards (1914-1919) by Brian Wade

|

|

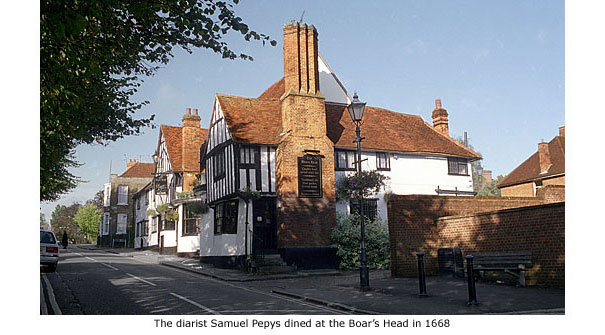

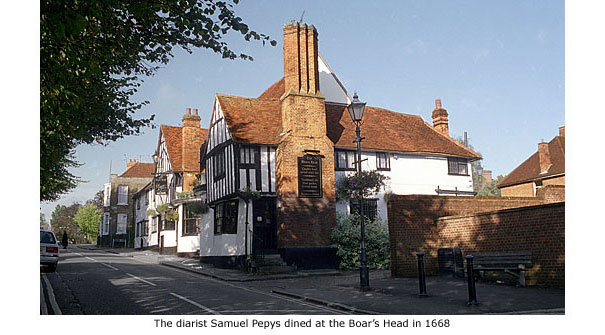

Through the centuries the address of the Boar's Head has frequently changed between Windill and High Street, and although placed in this history under Windhill it is actually in High Street (See Guide 3 – High Street). Records first mention this inn in 1630 but it was certainly here in the 15th century – the west wing having been dated at around 1420. This being the case, it was very likely the original Church House for St Michael’s and first used for the brewing of Church ales – a fund-raising event whereby wardens begged or bought malt to produce beer, and then sold it to the public to raise funds. Ales was the collective name given to any festive gathering or fund-raising event, among them: Clerks ales; Whitsun ales and Hocking ales. These events gradually died out, but were the forerunner of today's Church Bazaar. Records also show the Boar’s Head paid a rent of 2d. (approx. 1p) to the church in 1644. Through the centuries the address of the Boar's Head has frequently changed between Windill and High Street, and although placed in this history under Windhill it is actually in High Street (See Guide 3 – High Street). Records first mention this inn in 1630 but it was certainly here in the 15th century – the west wing having been dated at around 1420. This being the case, it was very likely the original Church House for St Michael’s and first used for the brewing of Church ales – a fund-raising event whereby wardens begged or bought malt to produce beer, and then sold it to the public to raise funds. Ales was the collective name given to any festive gathering or fund-raising event, among them: Clerks ales; Whitsun ales and Hocking ales. These events gradually died out, but were the forerunner of today's Church Bazaar. Records also show the Boar’s Head paid a rent of 2d. (approx. 1p) to the church in 1644.

With its three irregular gables and timber and plaster exterior, this inn is everything we have come to expect of a Tudor building. Inevitably, though, it has been subjected to some restoration and alteration. The quarter circle windows at the entrance were probably added in the 18th century and the inn’s original plaster covering was removed in the early 1900s to reveal the timber framework. Just to the left of the main entrance, high above the pavement, can be seen a filled-in medieval doorway.

Inside, an obligatory stuffed boar’s head surveys the bar from above the cavernous brick-built fireplace, which is further complimented by a large wooden mantelpiece. This is said to be part of the original Rood Loft beam from St Michael’s Church which, before the Reformation, supported the figures of Christ, St Mary and St John above the screen at the entrance to the chancel.

When the protestant Elizabeth I came to the throne in 1558 after the death of her catholic half-sister, Queen Mary, all articles associated with the Catholic faith were removed from churches throughout the kingdom. In St Michael’s this also included the Rood Loft, dismantled in 1564 and the timber sold off to local people. Church records show that one Robert Lewis paid the sum of 1s. 8d. (9p) for ‘a pece of Roode loft tymber’, but it’s not known if Mr Lewis was landlord of this inn at that time or, indeed, if the ‘pece of tymber’ sold is the very same that now acts as a mantelpiece above the fire.

Stories handed down through the years tell of a network of secret passages beneath Bishop’s Stortford’s streets, some of which are known to exist while others are simply the product of vivid imagination. In the cellar of the Boar’s Head there is most certainly a bricked-up archway, said to be the former entrance of a tunnel that linked to both the church and Waytemore Castle. No evidence of a tunnel has ever being found beneath the church to substantiate this, although to dig a subterranean passageway between the two would not have been impossible. Tunnelling towards the castle, however, would have been almost geologically impossible at that time, its long route having to pass through gravel, sand and clay and also beneath the castle’s moat.

During the mid 17th century the diarist Samuel Pepys regularly passed through Bishop’s Stortford and is known to have stayed at the Reindeer Inn at Market Square. However, after a ‘falling out’ with the landlady, Betty Aynsworth, he later frequented the Boar’s Head and is recorded as having dined here on 26 May 1668 (See Guide 2 – The Reindeer Inn).

Throughout the first half of the 18th century the inn was owned by the vicar of Standon, then for a time by licencees and others. In 1822 it came under the ownership of local brewers Hawkes & Co, and from around 1834 until about 1848, the landlord was Abraham Smoothy and his wife, Sarah. Born Sarah Wright in nearby Sawbridgeworth, she married Abraham in St Dunstan Church, Stepney, London, in 1831. When they left the Boar's Head they moved to Elmdon in Essex to become licencees of the Wilkes Arms public house, but within two years Abraham died. Instead of being buried in Elmdon his body was returned to Stortford to be laid to rest in St Michael's churchyard. Sarah remained as landlady of the Wilkes Arms until at least 1862.

Additional information about Abraham Smoothy and his wife is thanks to Ray Smith.

In common with many older buildings in the town, the familiar ghost of the Grey Lady has been seen here on several occasions (See Guide 6 – Ghosts of Stortford), and in 1991 the inn was almost destroyed by fire.

|

Through the centuries the address of the Boar's Head has frequently changed between Windill and High Street, and although placed in this history under Windhill it is actually in High Street (See Guide 3 – High Street). Records first mention this inn in 1630 but it was certainly here in the 15th century – the west wing having been dated at around 1420. This being the case, it was very likely the original Church House for St Michael’s and first used for the brewing of Church ales – a fund-raising event whereby wardens begged or bought malt to produce beer, and then sold it to the public to raise funds. Ales was the collective name given to any festive gathering or fund-raising event, among them: Clerks ales; Whitsun ales and Hocking ales. These events gradually died out, but were the forerunner of today's Church Bazaar. Records also show the Boar’s Head paid a rent of 2d. (approx. 1p) to the church in 1644.

Through the centuries the address of the Boar's Head has frequently changed between Windill and High Street, and although placed in this history under Windhill it is actually in High Street (See Guide 3 – High Street). Records first mention this inn in 1630 but it was certainly here in the 15th century – the west wing having been dated at around 1420. This being the case, it was very likely the original Church House for St Michael’s and first used for the brewing of Church ales – a fund-raising event whereby wardens begged or bought malt to produce beer, and then sold it to the public to raise funds. Ales was the collective name given to any festive gathering or fund-raising event, among them: Clerks ales; Whitsun ales and Hocking ales. These events gradually died out, but were the forerunner of today's Church Bazaar. Records also show the Boar’s Head paid a rent of 2d. (approx. 1p) to the church in 1644.