|

It would be natural to assume that Causeway ends at its junction with Dane Street, but it does in fact end at the river – the river forming the boundary between the town proper and Hockerill. Up until the 18th century this stretch of water was just one of many small tributaries of the river Stort that filtered off onto the Meads – the town’s flood plain. In the 12th century the Normans greatly increased the width and depth of one such tributary to form the moat that surrounded Waytemore Castle.

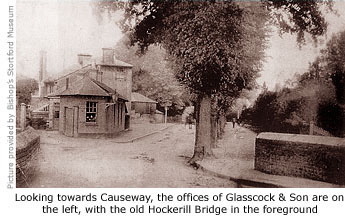

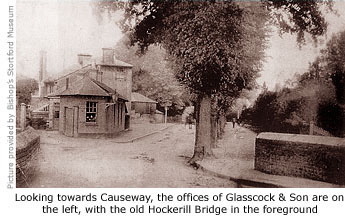

The bridge that spans the waterway at this point, built in the early 1960s when Causeway was widened, could best be described as ‘functional’ and easily missed. It replaced a narrower more conventional bridge, but what had been of adequate strength for horse-drawn transport was not suitable for heavy traffic. First mention of a bridge here was in 1350, referred to as Hokkerell Bregge, but it's likely that some form of construction had been in place long before that time to enable passage between the town and Hockerill.

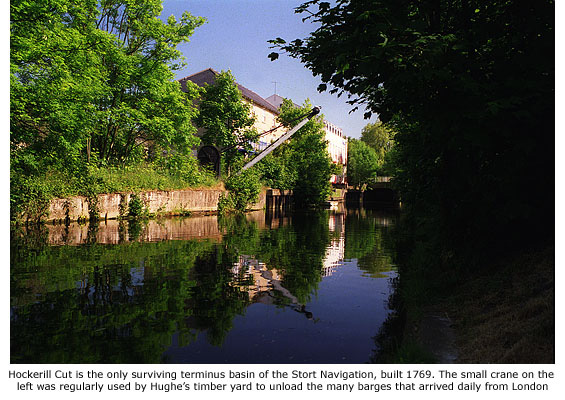

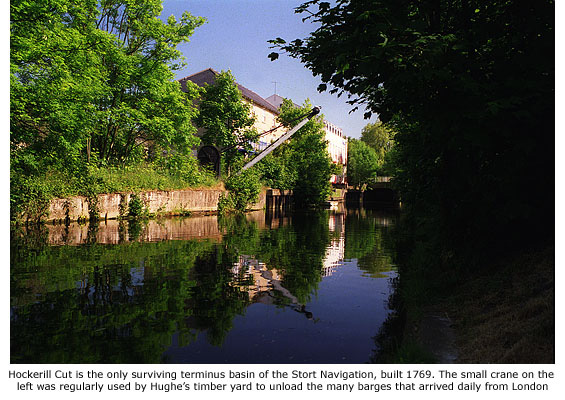

The stretch of water here is called Hockerill Cut, though there is uncertainty as to why it was so named. It could derive from the fact that at this point Hockerill is ‘cut’ off from the main town, but it's more likely the name originated from the time of canalisation when land was ‘cut’ away to make the tributary wider and suitable for use as a canal basin. The stretch of water here is called Hockerill Cut, though there is uncertainty as to why it was so named. It could derive from the fact that at this point Hockerill is ‘cut’ off from the main town, but it's more likely the name originated from the time of canalisation when land was ‘cut’ away to make the tributary wider and suitable for use as a canal basin.

Whatever the reason for its naming, Hockerill Cut survives as the town’s Navigation head and was where, on Tuesday 23 October 1769, the first barges to use the Navigation arrived from London; two decked out in colours and carrying 500 passengers, followed by a third filled with coal. Cheering crowds greeted their arrival, a 21-gun salute was fired from cannons placed at the Crown Inn, and the Royal Standard flew from the church spire and flagpoles erected here and all around the town. The chief engineer of the project, Thomas Yeoman, made a speech in which he declared ‘Now is Bishop’s Stortford open to all ports of the world’. Geographically his statement was correct but ‘perhaps’ a little optimistic.

Regardless, it was a day of tremendous celebration that culminated with a ball and party for dignitaries and a huge feast in North Street, large enough to feed 6,000 people. Sir George Jackson, one of the founders of the Navigation, kept a diary of events recording the building of the canal and made this entry regarding the night-time celebrations that very nearly got out of hand: Regardless, it was a day of tremendous celebration that culminated with a ball and party for dignitaries and a huge feast in North Street, large enough to feed 6,000 people. Sir George Jackson, one of the founders of the Navigation, kept a diary of events recording the building of the canal and made this entry regarding the night-time celebrations that very nearly got out of hand:

‘The table in the booth was scarce well covered, and the company set down before the crowd broke in and took all the meat away. It became a scramble after that. It was with great exertion that I served the wine. When this was a little appeased the bread was cut into lumps and given to the people and after this the ale, being hogsheads, was filled into two large tubs and carried into the streets, where people might drink that could. Some getting drunk soon and giving room to fear a riot, and one of the tubs, when full being thrown over, desisted from serving out the rest. However the whole confusion was ended without the smallest accident or quarrel that I have heard of.’

Although the canal ultimately saved Bishop’s Stortford’s malting industry it wasn’t a great success financially, ownership later passing through several hands (See Guide 11 – Stort Navigation). Each owner, however, continued to carry out necessary work, an example of which can be seen near to the bridge where steel supports, put in place in 1876 to strengthen the river bank, still bear the mark: RSN (River Stort Navigation) 1876.

A prominent feature on the western bank is a small 19th century crane, once used by Hughes timber yard for unloading barges arriving from London. This has recently been restored and returned to its original site on the river bank as a reminder of this area's history. MORE PICTURES

|

|

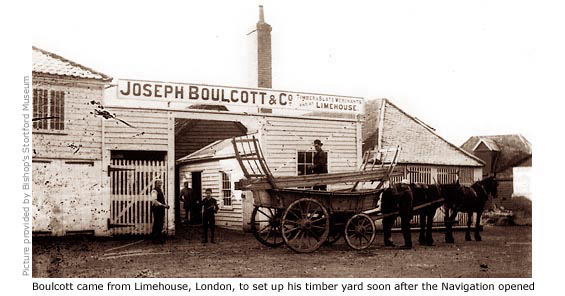

The Navigation was built primarily to carry the town's malt production, quickly and cheaply by barge to the metropolis. For one Londoner though, a timber merchant named John Boulcott with premises in London's dockland, it presented an opportunity to expand his business by setting up in Bishop's Stortford.

His timber yard at Narrow Street, Ratcliffe, included a wharf alongside a small waterway linking the Thames to nearby Limehouse Basin. This in turn was joined by Limehouse Cut, a waterway created through London's East in the mid 18th century as a short-cut for barges journeying between this part of the Thames and the river Lea. Along with the newly opened Stort Navigation that joined the Lea at Rye House, Essex, a direct route between Limehouse and Bishop's Stortford was created.

Leasing a piece of land alongside Hockerill Cut from the Church Commissioners, Boulcott then established a timber yard that he stocked with wood transported by barge from his London timber yard. It's unclear when Boulcott founded his London business, but he was advertising in directories from 1784 onwards. His eldest son, Joseph Crew Boulcott, later joined him in partnership and both are recorded at the Narrow Street premises in 1810.

The lucrative timber trade made John Boulcott a wealthy man. When he died in 1833 he left his two sons property in London, County Durham and Yorkshire, though strangely his will made no mention of the timber yard at Stortford. It is possible, of course, that this part of the business was turned over to Joseph before the will was made in 1832.

Joseph Boulcott continued to work at the Stortford timber yard until age and ill health forced his retirement, then returned to live in London making only occasional visits to the town. When he did he stayed at the Crown Inn. At his death in 1850, aged 67, the business passed to his friend Charles Cadman, but when he died unexpectedly it passed to two of his employees, Messrs Linington and Jeffrey.

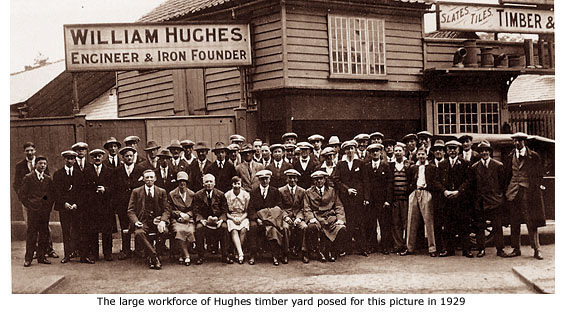

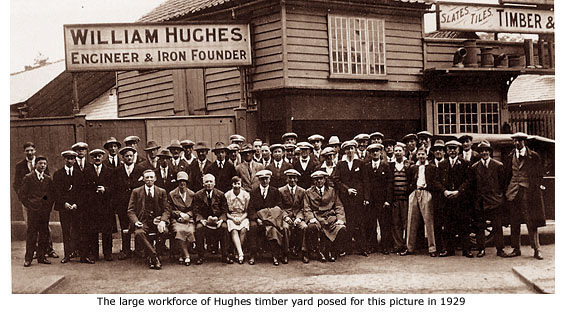

Prior to this date, in the mid 1830s, William Hughes from Northgate End (possibly the son of William Hughes who had a pump making business there in 1784) had purchased a piece of land adjoining Boulcott's timber yard on which he set up an iron foundry. At the same time he was appointed manager of Boulcott's. Prior to this date, in the mid 1830s, William Hughes from Northgate End (possibly the son of William Hughes who had a pump making business there in 1784) had purchased a piece of land adjoining Boulcott's timber yard on which he set up an iron foundry. At the same time he was appointed manager of Boulcott's.

His foundry made moulds for various domestic items, including school desks, but the most unusual commission he ever had was to make a replica of the Key of Hockerill. This larger-than-life key mysteriously disappeared in the 1800s while being transported from the Crown Inn to the Cock Inn, both at Hockerill crossroads, then finally came to light in Cambridge. The new owner was reluctant to give it up, but did give his permission for a replica to be made (See Guide 9 – The Cock Inn).

When Hughes died in 1851 he was succeeded as manager of Boulcott's by his son William Hughes II, and in 1898 owners Linington and Jeffrey were succeeded by their sons. In 1905 William Hughes II died and was replaced as manager by his son William Hughes III, and when he died in 1918 his son William Hughes IV took over the role. Both Linington and Jeffrey retired in 1925, giving Boulcott's timber business to Hughes who then amalgamated it with his foundry.

He regularly employed 60–70 men, taking on many part-time workers when times were busy to help unload the constant arrival of barges. Timber came mainly from Archangel in Russia, and despite the convenience and relative speed of road transport at this time, Hughes insisted on using horse drawn barges for transporting the timber from London's Surrey Commercial Docks to Bishop's Stortford, via the river Lea and Stort Navigation.

From the late 19th century the Hughes family occupied a house in the Causeway, but being so close to the river meant that flooding was always a serious threat. To safeguard themselves against the inevitable, a small trapdoor was built into the floor of the house making it possible for the owner to reach inside and feel the earth below. If the ground was damp it was time to take up the carpets and move upstairs!

William Hughes IV continued to run the business until his retirement in 1935, at which time it was sold to Ipswich importers, William Brown. They finally closed the timber yard around 1964 and William Hughes died in 1971, aged 91

The only surviving immediate member of the family was Miss Ruth G. Hughes, who died 2 March 2007, aged 95. Born in the family home at Northgate End in 1911, she attended former Chantry Mount School, worked as a matron in one of the houses at Bishop's Stortford College for 32 years, and lived in Bishop's Stortford for most of her life, latterly at Cradle End, Little Hadham.

My thanks to Anne Plumridge for details about the Boulcott family, and to Miss Ruth Hughes and Cedric Thomas for additional information about the Hughes family and the timber yard. MORE PICTURES

|

The stretch of water here is called Hockerill Cut, though there is uncertainty as to why it was so named. It could derive from the fact that at this point Hockerill is ‘cut’ off from the main town, but it's more likely the name originated from the time of canalisation when land was ‘cut’ away to make the tributary wider and suitable for use as a canal basin.

The stretch of water here is called Hockerill Cut, though there is uncertainty as to why it was so named. It could derive from the fact that at this point Hockerill is ‘cut’ off from the main town, but it's more likely the name originated from the time of canalisation when land was ‘cut’ away to make the tributary wider and suitable for use as a canal basin. Regardless, it was a day of tremendous celebration that culminated with a ball and party for dignitaries and a huge feast in North Street, large enough to feed 6,000 people. Sir George Jackson, one of the founders of the Navigation, kept a diary of events recording the building of the canal and made this entry regarding the night-time celebrations that very nearly got out of hand:

Regardless, it was a day of tremendous celebration that culminated with a ball and party for dignitaries and a huge feast in North Street, large enough to feed 6,000 people. Sir George Jackson, one of the founders of the Navigation, kept a diary of events recording the building of the canal and made this entry regarding the night-time celebrations that very nearly got out of hand: