|

So far as is known, parochial poor relief dates back to at least the 15th century. At that time help for the most needy was mainly given by the monasteries and some of the wealthier and more benevolent members of society, but as the medieval social structure broke down and the dissolution of the monasteries took effect in 1536, voluntary assistance gradually gave way to compulsory taxation administered at parish level.

Before this time legislation dealt mainly with beggars and vagabonds, the number of which increased dramatically after the plague of 1348–49. As the acute labour shortage inflated wages, Acts were passed to force all able-bodied men to work and thereby restore wages to former levels. But the plan wasn’t a great success. Many labourers simply worked in areas where the law was lax and many more resorted to begging, under the pretence of being ill or crippled.

Curtailment of this practice was attempted in 1388 with the Statute of Cambridge. This restricted the movement of all labourers and beggars by making each county (Hundred) responsible for its own ‘impotent poor’ i.e. those who were incapable of work because of age or infirmity. Lack of enforcement limited the Act’s impact but further legislation followed in 1494 with the purpose of severely punishing ‘idle’ vagabonds and beggars. Curtailment of this practice was attempted in 1388 with the Statute of Cambridge. This restricted the movement of all labourers and beggars by making each county (Hundred) responsible for its own ‘impotent poor’ i.e. those who were incapable of work because of age or infirmity. Lack of enforcement limited the Act’s impact but further legislation followed in 1494 with the purpose of severely punishing ‘idle’ vagabonds and beggars.

The range of penalties included whipping for the first offence, the loss of an ear for the second, and hanging for the third. But such legislation was severe even for that age, and totally inconsistent. While the Church was preaching the duty of alms-giving as a Christian virtue, the state was punishing those asking for alms as a capital crime.

The Tudors, under Henry VIII (1509–47), created a machinery of government that depended on the support of the propertied section of the population: but poverty still remained a problem. In 1535 another Act attempted to deal with this by making every parish responsible for its poor by means of charitable alms i.e. money given voluntarily by those in a position most able to afford it. The system failed and in 1552 a further Act ordered the appointment of two collectors of alms in each parish, who would ‘politely' demand of each man and woman what they or their charity would be contented to give weekly to the relief of the poor. This system also proved fallible and by 1563 Justices of the Peace were empowered to levy contributions and imprison anybody who refused.

The Statute of Legal Settlement enacted that sturdy beggars could be branded or made short-term slaves, and that no pity should be shown to vagrants. A more positive aspect of the Act was the building of cottages for the impotent poor who were to be ‘relieved or cured’.

In 1564 another Act was aimed at suppressing roaming beggars by empowering parish officers to ‘appoint meet and convenient places for the habitations and abidings’ of such classes'. This was the first reference to what would ultimately be termed workhouses.

In 1598 Queen Elizabeth I’s government passed the Act For the Relief of the Poore; requiring every parish to appoint an Overseer of the Poor whose duty it was to find work for the unemployed and set up parish-houses for those who were incapable of supporting themselves. But this was soon considered an unsatisfactory way of looking after the poor and in 1601 Elizabeth I’s Poor Law Act made the poor the responsibility of the Parish. It empowered parish overseers to raise money for poor relief from parish residents according to their ability to pay – a form of local income tax that would eventually evolve into the rating system. The sick, aged or orphans were to be cared for by the parish, while the able-bodied poor or unemployed would be punished in houses of correction because they themselves would be responsible for not having a job.

Local authority at that time consisted of the Parish Vestry, formed of four principle officers elected by the rate (or tax) payers. They were: a Churchwarden; a Constable; a Surveyor of the Roads and an Overseer of the poor. This system also worked well for a time but as the population grew it failed through neglect and corruption, in particular the Overseers of the poor who were often more generous to themselves than the poor they were meant to look after.

In general, the poor were regarded as a nuisance and whenever possible were driven away so that another parish might assume responsibility for them. Women of childbearing age were particularly vulnerable to this treatment because any illegitimate children would increase the burden on the parish. This practice was curtailed in 1662 by the Act of Settlement, which deemed the parish a person was born in should be solely responsible for him/her unless they had lived or worked in another for more than a year. This rarely happened as most employers gave contracts of work for only 364 days.

A further act ordered that from 1 May 1697, poor persons could enter any parish so long as they carried with them their parish of settlement certificate, guaranteeing to receive them back again if they proved chargeable. To denote their place of origin, paupers and all family members had to wear a badge made from red or blue material in the shape of a Roman ‘P’, together with the first letter of the name of the parish where they lived. Any pauper who didn’t display the badge could either lose their relief or be sent to a house of correction. There they would probably be whipped and sentenced to three weeks hard labour.

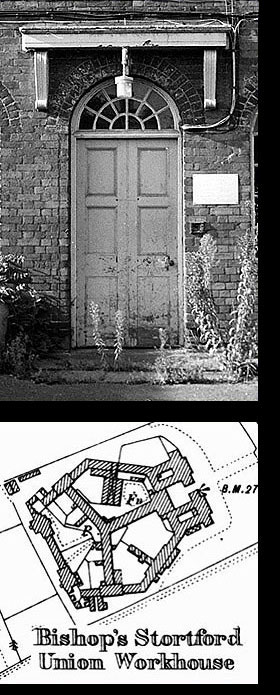

Sir Edward Knatchbull’s Amendment Act of 1723, relating to the settlement, employment and relief of the poor, encouraged parishes to put the village poor to work, usually in menial jobs, in the belief they could pay for themselves. More importantly, the Act also ordered the building or renting of workhouses, to be set up by parishes either singly or in combination with neighbouring parishes. Such places were conceived to be a deterrent and only available to those who wouldn’t conform to the work ethic or were desperate enough to accept its harsh regime. Gilbert’s Act of 1782 attempted to improve the conditions paupers had to endure in workhouses by appointing inspectors. Other changes included the ruling that paupers couldn’t be sent to a workhouse more than 10 miles from their parish and that the ‘badge’ could be discarded if the wearer was of good character.

The year 1795 witnessed the arrival of the Speenhamland ‘Act’ – not an Act of parliament but a decision made by parish Magistrates meeting at Speenhamland in Berkshire. They agreed to supplement low wages of men in work out of the poor rate, on a scale that varied with the price of bread and number of children. Many other counties soon copied the idea but this ultimately led to all able-bodied labourers believing they were also entitled to parish relief when out of work. The result was a depression of wages in agricultural areas, with the rest of the community subsidising the farmers.

Arguably, this was the straw that broke the camel’s back and the whole system was, by now, in total chaos. In the coming years the government set up a series of commissions but their conclusions for reform were mostly ignored. Then, in the late 1820s there was a growing dissatisfaction from the land-owning classes who bore the brunt of the growing poor-rate burden. Coupled with unrest among the poor, particularly in rural areas where rioting broke out and poorhouses were attacked, the British Government finally decided to appoint a Royal Commission to review the system.

In 1832, under the chairmanship of the bishop of London, a detailed survey was conducted on the state of poor law administration and a report prepared. This was largely the work of just two of the Commissioners, Nassau Senior and Edwin Chadwick. The report took the view that poverty was essentially caused by the indigence of individuals rather than economic and social conditions. Quite simply, paupers claimed relief regardless of their merits. Large families got most, which encouraged improvident marriages; women claimed relief for bastard children, which encouraged immorality; labourers had no incentive to work, and employers kept wages artificially low as workers were subsidised from the poor rate.

In 1834 the Commission’s findings resulted in The Poor Law Amendment Act; an act for 'the Amendment and better Administration of the Laws relating to the Poor in England and Wales.' On reflection, it can be counted as one of the most significant pieces of social legislation in British history, sweeping away the accumulation of poor-laws going back five centuries and replacing them with a national system for dealing with poverty and its relief, based around the Union workhouse. In 1834 the Commission’s findings resulted in The Poor Law Amendment Act; an act for 'the Amendment and better Administration of the Laws relating to the Poor in England and Wales.' On reflection, it can be counted as one of the most significant pieces of social legislation in British history, sweeping away the accumulation of poor-laws going back five centuries and replacing them with a national system for dealing with poverty and its relief, based around the Union workhouse.

Under the new laws, people generally only ended up in the workhouse if they were too poor, too old, or too ill to support themselves and had no family, willing or able, to provide care for them. But it also became a refuge for orphans and many unmarried pregnant women whose family had disowned them. And prior to the establishment of public mental asylums in the mid-nineteenth century, it was also a place where the mentally ill and mentally handicapped poor were consigned.

To spread the cost of looking after paupers the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 enabled parishes to group together in Unions, with the proviso that no assistance, except medical care, would be granted to able-bodied persons outside of a workhouse. The Act also directed that each Union was to be run by a board of Guardians elected by the ratepayers. Three commissioners in Somerset House, London, had almost dictatorial powers to compel the Guardians to execute their policy.

Unions built workhouses into which all poor people would go, breaking up families and making life as uncomfortable as possible for them in order that they realise it would be far better to find employment than be cared for by the parish. For nearly seventy years the Law caused untold misery to thousands of people.

But by 1900 the harshness of the workhouse regime was under review and the government finally relented to allowing old people to receive adequate relief from the rates while still living in their own homes. Between 1905–09, a Royal Commission on the Poor Laws advocated complete abandonment of the 1834 principles, and although workhouses were to remain in operation, life inside did become a little more tolerable. Living conditions and diet were generally healthier and luxuries such as books, newspapers and toys for children became the norm. Despite this, in 1926 there were still 226,000 inmates occupying approximately 600 workhouses, each with an average population of about 400 inmates.

Three years later the Local Government Act finally abolished workhouses altogether, and on 1 April 1930 the responsibilities of 643 boards of Guardians in England and Wales were officially handed over to county borough and county councils. As part of their new image the name Union Workhouse was changed to Public Assistance Institution, but in reality it meant little more than the abolition of uniforms and slightly more freedom for inmates. Not until 1947, when the National Assistance Act made ‘provision’ a national responsibility in which financial assistance would be provided for anyone who could prove they were in real need, did things really start to improve.

|

|