|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

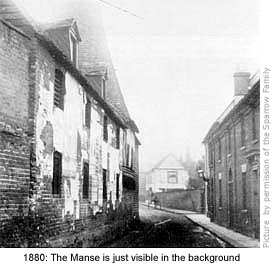

The Manse

|

|

The definition of ‘Manse’ is ‘an ecclesiastical residence; especially that of a parish minister of the Church of Scotland’. With this in mind, and the fact that Scotland is some way off, it’s something of mystery why a large house that once stood opposite the church was actually called the Manse. It is also believed that not one minister attached to the Congregational church ever lived in the house. The definition of ‘Manse’ is ‘an ecclesiastical residence; especially that of a parish minister of the Church of Scotland’. With this in mind, and the fact that Scotland is some way off, it’s something of mystery why a large house that once stood opposite the church was actually called the Manse. It is also believed that not one minister attached to the Congregational church ever lived in the house.

The Manse commanded a large plot of land – now part of Waitrose’s car park – that stretched as far as the original course of the river Stort and was surrounded on all sides by a high brick wall. Part of this still stands alongside the footpath bordering the car park, and three large trees that stood in its garden are still evident near the top of the car park, close to Water Lane.

The outward appearance of the Manse was Georgian and not dissimilar to that of nearby Guild House, but its facade belied its true age. The interior was a maze of passages and rooms at different levels, and all with varying ceiling heights. In 1966 it was said to be Bishop’s Stortford’s oldest building, and then demolished that same year. 'New Age' planners of the time had little sentiment for anything old, nor did the town council who sanctioned its demise to make way for the present car park. Ministerial intervention did delay the end for a short while but when a preservation order failed to materialise, the Manse disappeared in a pile of dust.

The fact that its main claim to fame was significant in the town’s history seemingly meant nothing. In 1850 the Manse became the schoolhouse of the non-sectarian Bishop’s Stortford Collegiate School, founded by the vicar of the Congregational church, Rev Hurndall. So successful did it prove that in 1852 the school moved to much larger premises at Maze Green Road, and in 1868 was inaugurated as a public establishment named the Nonconformist Grammar School. In 1903 it was renamed the Bishop’s Stortford College. (See Guide 5) MORE PICTURES

|

|

|

|

In the Middle Ages Water Lane was a slum area, the poor of the town living in run-down houses and shelters that stretched from here to the river bank – its original course at that time cutting through the middle of, what is now, Causeway car park. It was the necessity of water to the tanning trade that made Water Lane the centre for the town’s tanning industry in the 15th century. In the Middle Ages Water Lane was a slum area, the poor of the town living in run-down houses and shelters that stretched from here to the river bank – its original course at that time cutting through the middle of, what is now, Causeway car park. It was the necessity of water to the tanning trade that made Water Lane the centre for the town’s tanning industry in the 15th century.

Barrett Lane is named in memory of Alfred Slapps Barrett. In the latter half of the 19th century it was named Dodd’s Lane in memory of Charles Dodd, and before that it was Cross Street. Long before that, though, it was Dog and Bear Lane – a reference to the 17th century Dog and Bear alehouse that stood at the top of the lane. This was replaced by a property that in the 1800s became Summers Print Shop, as well as the town post office, then later a grocery shop owned first by Charles Dodd and then by Alfred Slapps Barrett (See No 18 North Street).

Charles Dodd also owned property behind his North Street shop that included warehouses and a malting office occupied by Messrs Patmore & Case. These same premises were later used by the auctioneering business of Summers, Sworder & Summers (See No 17 North Street), possibly for storage and as an auction house.

In the late 19th century Frank Fowler owned a butchers shop where Lloyds Bank now stands in North Street, and the site of the small car park behind the bank was once his stable and slaughterhouse.

Directly opposite Barrett Lane is Guild House, currently an estate agent but originally built in the 16th century as a private residence. Why it was called Guild House is a mystery as it has no known affiliations with previous town guilds. Simply constructed with a cellar and attic, the house was re-faced in the 18th century and the pedimented Ionic door case added. The southeast wing at the rear was built at an unknown date and the less elegant northeast wing, with flat roof, added in more recent years.

The entrance at the left of Guild House leads to the Congregational Church Hall, built on the previous site of a malting. In the 1880s, membership of the Congregational church Sunday School numbered over 400 but with no meeting place to call their own, children gathered each Sunday in the British school at Northgate End. In an attempt to rectify the situation Sir Walter Gilbey gave, as a gift in 1895, the plot of land between the church and Dodd’s Lane (now Barrett Lane) for the building of a new hall to accommodate the Sunday school.

It was thought his generosity might also extend to help fund the hall itself, but it didn’t and the project came to nothing. Hopes of a new hall were again raised in 1907 when the chance came to buy a house and malting that stood close to the church for £900. But when both buildings proved unfit for adaption the Rev John Wood instigated a fund to build a new hall on the site capable of holding the Sunday school's large membership. The money was raised and in 1914 the foundation stone laid, the new hall opening the following year on the 15th April.

But by this time the First World War had started, and in conjunction with the Sunday school the hall was used as a social and cultural centre for troops stationed in this area. It was through this connection that it became known as the ‘Institute’, a title that lasted until 1960 when the original name, ‘Congregational Church Hall’, was reinstated.

In its time the hall has been used for concerts, amateur theatre, public meetings and as a Welfare Centre, but in 1921 it became the first home of Waterside School – originally a Preparatory school within Bishop’s Stortford College run by a Miss E J Blandford. Wanting to start a small private prep school away from the college, though still be affiliated to it, she gained the full support of headmaster F S Young and began here with just two classrooms. It was named Waterside because at that time the river ran right past the front of the building. The school's popularity was so great that by 1924 larger premises were needed, and three rooms were accommodated on the top floor of Church Street’s Technical Institute to act as classrooms (See Guide 15 – Church Street). In its time the hall has been used for concerts, amateur theatre, public meetings and as a Welfare Centre, but in 1921 it became the first home of Waterside School – originally a Preparatory school within Bishop’s Stortford College run by a Miss E J Blandford. Wanting to start a small private prep school away from the college, though still be affiliated to it, she gained the full support of headmaster F S Young and began here with just two classrooms. It was named Waterside because at that time the river ran right past the front of the building. The school's popularity was so great that by 1924 larger premises were needed, and three rooms were accommodated on the top floor of Church Street’s Technical Institute to act as classrooms (See Guide 15 – Church Street).

The small terrace of houses to the right of Guild House was converted for use by the Lemon Tree restaurant in 1996, and the yellow-bricked building opposite (built in the 1980s) stands on the site of a malting that once stretched as far as the Star Inn at the end of the lane. An opening on the right – a private access – gives a view of the original bay window at the rear of Mr Boardman’s former house, now Boardman’s shop. MORE PICTURES

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Leather Industry

|

|

|

|

|

|

In the 15th century Water Lane was the centre of the town's leather industry: at one time accommodating no less than thirteen tanneries. The importance of the trade in the town can be judged by the number of times the surnames Tanner and Skinner occur in past court rolls and churchwardens’ accounts, as well as in the naming of two public houses. Market Square was once home to the Curriers Arms (See Guide 2), and in London Road there still exists the Tanners Arms (See Guide 12). The only downside to this industry was the foul stench emitted from the tanning pits, which in Stortford’s case was compounded by the constant smell emitted from the kilns of local maltings. Together, they created odours so revolting that the district was best avoided.

The discovery of leather dates back to primitive man. Wild animals were hunted primarily for food, but it didn’t take long to discover that the skins of dead animals could be used as crude shelters and for clothing and footwear. But without treatment, pelts very quickly putrefied and became useless. One method used to preserve skins was to stretch them and rub on fats and animal brains while they dried. It's thought man first discovered how to make leather after leaving animal skins on a wet forest floor; the chemicals released by decaying leaves and vegetation causing tanning to occur naturally. Thereafter skins were treated with an infusion of tannin – a cocktail of different barks, leaves and fruits from certain trees and plants.

The earliest record of the use of leather for clothing comes from cave paintings created between 250,000 and 200,000 years ago, discovered near Lerida in Spain. The Egyptians, ancient Greeks and Romans used leather extensively for clothing, sandals, water carriers and military equipment, and ancient Britons used it to cover the hulls of small boats known as coracles.

But it was the early invaders of this country, especially the Romans, who introduced the manufacture of leather – a craft so well perfected by monks in religious communities that they became experts in utilising it as parchment for writing purposes. By the Middle Ages the manufacture of leather had spread throughout the land, most towns and villages with access to a river or stream having their own tannery.

Tanning is the conversion of the skin or hide into leather. It was traditionally done by dusting the rawstock with ground-up tree bark (usually oak) and then immersing it in a shallow pit or vat containing a fermenting solution of organic matter. The bacteria that naturally grew attacked the skin, loosening hair or wool and some fats. Further ground bark was added until the tanning solution penetrated the skin completely – a process that could take up to two years for the thickest hides. Any remaining hair or fat was removed with a blunt stone or wooden scrapper and the leather then hung for several days in open sheds.

With the tanning process complete it was then the turn of the curriers to dress tanned hides and turn them into supple pieces of leather. This was done by paring or shaving the leather to a level thickness, colouring it, treating it with oils and greases, then drying and treating the grain surface with waxes and proteins. Finally, shellac was used to produce attractive finishes. Later use of earth salts containing alum as a tanning agent produced soft white leather that could be dyed with naturally occurring dyestuff in various plants. In the Middle Ages the finest shoe leather came from Cordova in Spain, which is why shoemakers in Britain became known as Cordwainers. Only those who repaired shoes were called Cobblers.

During the reign of Edward III (1327–1377), and probably under the aegis of the Church, curriers were among the first trades’ people to form exclusive trade organisations, known as guilds. James I granted their governing charter in 1605.

The Industrial Revolution of the 18th and 19th century created an even greater demand for leather, but the discovery and introduction of base chemicals like lime and sulphuric acid signalled the end for traditional tanning and leather production. By the end of the 19th century modern requirements in fashion demanded softer more supple leather, which traditional vegetable tanned leather proved too hard and too thick for. Instead, the use of the salts of the metal Chromium was adopted and chrome tanning became the tannage for modern footwear and fashion leathers. Today, curriers have very little practical connection with the trade, although the Guild of Curriers does still exist after almost 700 years.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|