|

Arthur Capel’s son, also Arthur, was born in 1631, 18 years before his father’s execution. In April 1661, soon after the Restoration, Charles II made the young Lord Hadham, Viscount Malden and Earl of Essex, in recognition of his father’s loyalty to Charles I. The title is still held by the head of the Capel family.

Many Puritans showed their disgust at having Charles II on the throne by emigrating to America, some founding the settlement, Haddam, in New England. Many Royalists, however, would have been celebrating their return to power in the Banqueting Hall at Hadham in Hertfordshire. Arthur lived at the house until 1668, the year of his eldest son’s death, and then moved to Cassiobury, his mother’s estate near Watford.

He was by nature an antagonist and frequently voiced his feelings against Catholicism, court life, and royal prerogative. He did, in fact, alienate himself from Charles II because of his views but was, never the less, appointed to a succession of Offices. In 1672 he succeeded Berkely as Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland, where he was said to ‘have behaved with honour and integrity’, and grew to love the country. He purged the country’s finance administration, repelled attempts to exploit the Irish land market and, ironically, endeavoured to improve the conditions of Roman Catholics. He was recalled to England in 1677 but always hoped to return to Ireland.

When Charles II succeeded to the throne he had no theological convictions, but with a sense of history he wanted to restore the Church of England, albeit with some religious tolerance towards Puritans. But what the English people feared most were a Catholic King and a return to Popery. It never seemed likely that Charles would produce a ‘legitimate’ heir, which meant that his brother James, a Catholic convert, would succeed him.

Capel was a staunch protestant and, politically, his attitude became more and more intolerant of the Roman Catholic flavour of the court. He was among the many supporters of Charles’s illegitimate protestant son, James Scott, Duke of Monmouth, to succeed to the throne. In 1678 he was a member of the Triumvirate that dominated policy at the time of the Popish Plot; a fictitious but widely believed plot fabricated by Titus Oates, who revealed that Jesuits were planning to assassinate Charles II in order to bring his brother James to the throne.

Between March and November 1679 Capel was lord of the treasury and a member of the Privy Council. He worked with the earls of Halifax and Sunderland, supporting Halifax’s scheme to impose statutory limitations should the King’s Roman Catholic brother, the Duke of York (afterwards James II) succeed to the throne.

Later that year he became more fervent in his views and joined Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury, who led a campaign for parliament to pass an Act of Exclusion, which, in effect, would prevent James from succeeding Charles. Shaftesbury was a parliamentary tactician in the Cromwellian mould and fought a campaign so intense and so well organised it became the embryo of the two-party political system we know today. Supporters of Charles’s illegitimate son became known as Whigs and supporters of his brother (the gentry), were known as Tories – at that time, names also given respectively to Scottish outlaws and Irish rebels. In the event, the vote (in November 1680) was lost because Charles had more than enough support in the Lords to defeat it.

In 1683 a group of extremists formed a plot to assassinate the King and his brother on their return to London from the races at Newmarket. The route, along the Newmarket Road, passed Rye House in Hertfordshire (owned at the time by Hannibal Rumbold, a former Roundhead officer) and it was here they were meant to meet their fate. Fortunately, for both, a fire at the racecourse forced the royal party to leave for London earlier than expected, and in the event the assassination attempt came to nothing.

Some weeks later government informers revealed the plot and seven suspected prominent Whigs, among them Arthur Capel, were arrested and imprisoned in the Tower of London. One of the suspects, Lord Howard, confessed to the crime immediately and, soon after, Capel was found in the Tower with his throat cut. The wound was inflicted with such ferocity that it was never clear whether he had taken his own life or was murdered. If it was suicide, his motive may well have been to prevent loss of his rights for committing treason, thus preserving his titles and his estates for his family.

The attempt on the King’s life later resulted in the execution of Lords Algernon Sydney and William Russell, along with one Richard Rumbold, who was hung drawn and quartered - one quarter of which was exhibited in Bishop’s Stortford (possibly because of Capel’s past link with the area) as an example and a warning.

|

|

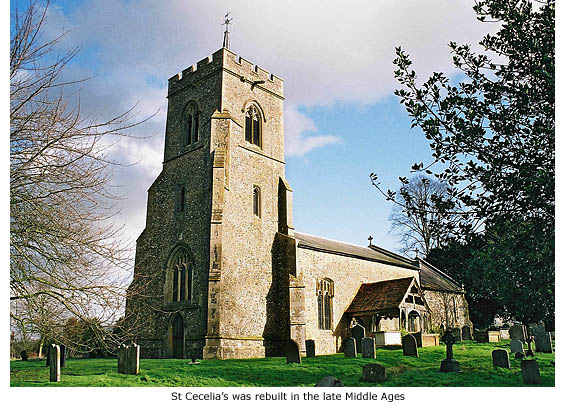

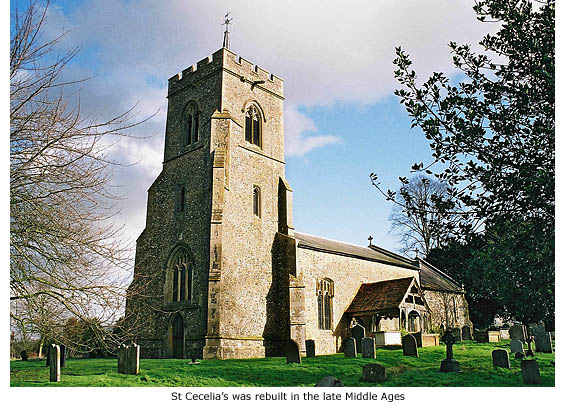

St Cecelia’s, the church of Little Hadham, is reached by travelling west along the A120 and then turning right into Church End, just before the village of Little Hadham. Built in the late 14th and early 15th century, St Cecelia’s probably stands on the site of an earlier church that fell within the bounds of the manor of Hadham Hall.

The Saxon lords who first owned the manor also owned the advowson of the parish i.e. they had the right to appoint the clergyman to it, but this changed in 1086 when the Baud family held the manor, and they appointed the clergy. This continued until 1276 when Sir Walter Baud sold the advowson to the Bishop of London for the sum of £20. The family still maintained a close association with the church and possibly paid for its rebuilding in the late middle ages – the church that stands today. Many of the Baud family are buried here.

The Capel family who bought the manor in 1504 also established a close association with the church, enlarging it in the late 16th century by building the north transept. An ancient footpath that leads from Hadham Hall directly to the transept’s east door, suggests it was purpose built for use by the numerous employees of the mansion, which Capel rebuilt to coincide with Queen Elizabeth I’s visit in 1578.

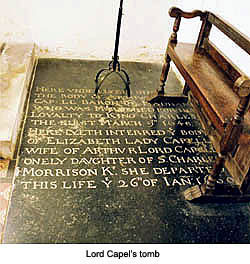

The Capel family vault, originally under the altar, was opened in 1883 during restoration work and the two memorial slabs in memory of Arthur Capel, his wife and son, were moved to their present position either side of the altar.

• An excellent booklet, written by Peter Marshall, gives far greater history and detail and is available inside the St Cecelia’s for the price of a donation towards church funds.

|