|

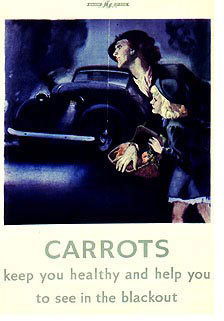

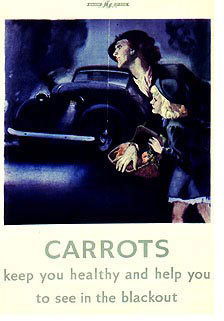

None were sorry to see the back of 1939, but those wishing for a peaceful and happy new year were in for a rude awakening. On 1 January conscription was extended to all men aged between 20 and 27, and on 8 January food rationing was introduced – starting with butter, sugar and bacon. Other foods were soon to follow, as was the rationing of fuel and clothing. Also of little cheer was news that since the start of blackout regulations *4,133 people had been killed on Britain's roads, 2,657 of which were pedestrians. 30,000 had been injured.

*At this time road fatalities were nearly twice as many than had been killed by enemy action.

The snow and freezing conditions that affected Britain and Europe in December, continued into January – the end of the month proving to be this country’s coldest since 1894. The British people, who only a few months earlier had prepared themselves for annihilation from air attacks, now found themselves having to endure the petty miseries of the blackout, burst water pipes, milk freezing on doorsteps and no coal supplies. The Thames froze over, 1500 miles of railtrack was impassable, villages were cut off, and shops were bare of vegetables because they couldn't be dug from the frozen earth.

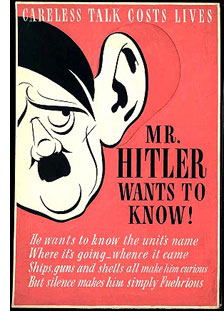

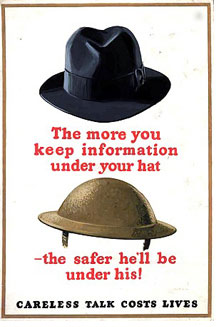

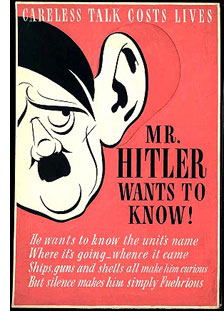

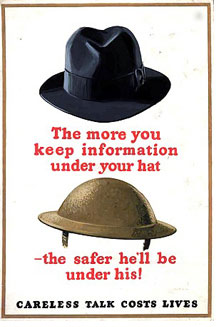

On 6 February the 'Careless Talk Costs Lives' campaign was launched; on 22 February two IRA bombs exploded in London, and on 11 March all meat was rationed. On 6 February the 'Careless Talk Costs Lives' campaign was launched; on 22 February two IRA bombs exploded in London, and on 11 March all meat was rationed.

But still no attack came and as the long, cold winter finally gave way to Spring, thousands more evacuees returned to their city homes. Then on 9 April, in a surprise attack consistent with their Blitzkrieg tactics, German Forces stormed into Norway and Denmark. Their successful invasion marked the end of the so called Phoney War and the start of war in western Europe. On the Home Front, however, the public remained largely unaffected by all this for another month.

17 April: The film 'Gone With The Wind' starring Clark Gable and Vivien Leigh, was released in the UK

23 April: Budget Day. Tax on beer raised by 1d a pint, whiskey up 1s. 9d and postage up 1d

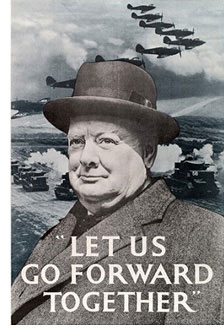

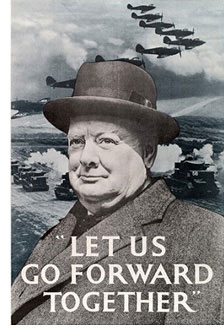

On 9 May the age for conscription in Britain rose to 36, and on 10 May German Forces turned their attention towards Holland, Belgium, Luxembourg and France. That same day Neville Chamberlain resigned as Prime Minister and Winston Churchill took his place. Hitler's formidable invasion of the Netherlands and subsequent push into western Europe now made war a stark reality for the British people.

On 11 May the King signed a proclamation cancelling the Whitsun Bank Holiday, and on 13 May (Whit Monday) Churchill addressed the House for the first time as Prime Minister. He told assembled MPs he had nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat, that his only policy was to wage war and his only aim was victory.

There followed on the evening of 14 May an urgent appeal from the British foreign secretary Anthony Eden, broadcast by the BBC, asking all men aged between 17 and 65 and not already serving in the armed forces, to become part-time soldiers. The response was astonishing. Within 24 hours of the appeal, over 250,000 men had applied to become Local Defence Volunteers.

15 May: Holland surrendered to Germany

20 May: Germans were on the coast of France looking across the English Channel

22 May: The entire British fighter force of 300 planes was withdrawn from France

That same month there was some concern about the activities of the supposed *Fifth Column in Britain, and rumours of German Fifth Columnists being parachuted in to help undermine the war effort. The threat was real, but true to form the British sense of humour shone through – political cartoonists and satirists having a field-day with the subject. It was even parodied by the H&E Observer's gardening expert, Roy Hay. In his column dated 25 May, under the headline 'Look out For Parachute Troops', he wrote 'This is the time of year when all sorts of 'fifth columnists' of the insect world try to wreck all the good work you have put in during the winter months. The worst offender is the Flea beetle.. '

*Fifth Columnist is the term used for a group within a nation that sympathises with and secretly works with the enemy

Nazi Germany's surprise invasion of the Low Countries and France, outnumbered and so overwhelmed the British Expeditionary Force that they were forced to retreat back to the small Channel port of Dunkirk where they remained trapped on the beaches. The subsequent evacuation by the Royal Navy, starting on 26 May, of over 338,000 Allied troops back to England also owed much to civilians in their 'little boats', but all of the expeditionary force's military hardware was lost. Nazi Germany's surprise invasion of the Low Countries and France, outnumbered and so overwhelmed the British Expeditionary Force that they were forced to retreat back to the small Channel port of Dunkirk where they remained trapped on the beaches. The subsequent evacuation by the Royal Navy, starting on 26 May, of over 338,000 Allied troops back to England also owed much to civilians in their 'little boats', but all of the expeditionary force's military hardware was lost.

The rescue of so many was hailed by the government and press as a victory, though it was in fact a humiliating defeat.

German bombing of Paris on 3 June prompted the British Government to pass a law requiring all householders in possession of an Anderson shelter to have them erected and earthed-up by 11 June. On 10 June Italy declared war on Britain and France, and on 17 June France surrendered to Germany. With the enemy now camped 30 miles across the Channel, war was suddenly a lot closer to home and a second evacuation moved over 200,000 school children away from the most vulnerable areas of possible invasion in southern and eastern England. The Germans consolidated their positions and the British prepared for invasion – the first such threat since the days of Napoleon in 1804.

Such depressing events are usually synonymous with grey, cold wintry weather, but June heralded the start of a truly glorious British summer. Clear blue skies were the norm every day and a top temperature of 90 degrees F (32C).

One reader of the H&E Observer wrote that he was worried by the suggestion in the national press that church towers should be used as lookout posts for home defence, reasoning they could then be termed as 'military objects' and therefore vulnerable to attack and destruction. Winston Churchill, in his speech to the nation on *18 June, put things into perspective for the concerned gentleman '..the Battle of France is over – I expect the Battle of Britain is about to begin.'

Perhaps in response to Churchill's speech, that night the Luftwaffe sent 120 bombers to attack eastern England, which included Cambridge. Nine people were killed when a row of houses was destroyed there.

In fact, Britain was now extremely vulnerable to attack by the Luftwaffe. The battle for France had left Fighter Command with just 768 planes in operational squadrons, of which only 520 were fit for operations. Matters weren't helped by replacement aircraft from North America taking so long to produce, forcing Britain to fight with only what its own factories could produce. In fact, Britain was now extremely vulnerable to attack by the Luftwaffe. The battle for France had left Fighter Command with just 768 planes in operational squadrons, of which only 520 were fit for operations. Matters weren't helped by replacement aircraft from North America taking so long to produce, forcing Britain to fight with only what its own factories could produce.

Government finances were also stretched to the limit, so at the end of June the newspaper magnate Lord Beaverbrook, who was also Minister of Aircraft Production, instigated the *'Spitfire Fund' – a fund into which individuals, companies, organisations or towns could donate money to buy replacement fighters. A nominal sum of £5,000 was quoted as the cost of a Spitfire, though the true cost was more like £15,000. Nationwide, the fund raised an astonishing £2.5 million in the first six weeks, although Bishop's Stortford's objective to raise £7,500 proved too optimistic. When the fund closed on 31 January 1941, donations from public collections and private donations amounted to just £3,084. 10s. 6d.

*Most of the money raised through the fund went to build Spitfire Mark IIs that were introduced in late 1940, early 1941

In the meantime, preparations to repel a full-scale invasion of the British mainland were hastened on 30 June when German troops landed on the Channel island of Guernsey. In towns and cities, iron in any form of gates and railings was removed for salvage and in rural areas pillboxes were built and anti-tank traps put in place. All signposts and milestones were removed or defaced.

In order to save roughly a thousand tons of copper a year, essential for munition making, June also saw the government suspend the minting of pennies. Pennies were made from bronze, which were nearly all copper. More economical to make was the twelve-sided threepenny bits, which people were urged to use instead.

Locally the RAF chose a former First World War airfield on the outskirts of Mathams Wood at Thorley as a suitable landing ground for No 2 (Army Cooperation) Squadron – within months extending it to 77 acres. It then became RAF Sawbridgeworth for the duration of the war. (For a brief history of the airfield see Thorley) An ammunition dump was sited in the spinney at Henley Hearne spring, Thorley.

Haymeads hospital became an annexe for the London Hospital, caring for walking wounded soldiers, at the same time being expanded to take casualties from any future bombing. The chance of London hospitals being bombed at this time was extremely high, so to protect expectant mothers the War Office requisitioned many large properties outside of London for use as maternity hospitals. Locally, this included *Twyford House at Pig Lane, where it is said 693 babies were born between 1940 and the end of the war (See Thorley Guide). Haymeads hospital became an annexe for the London Hospital, caring for walking wounded soldiers, at the same time being expanded to take casualties from any future bombing. The chance of London hospitals being bombed at this time was extremely high, so to protect expectant mothers the War Office requisitioned many large properties outside of London for use as maternity hospitals. Locally, this included *Twyford House at Pig Lane, where it is said 693 babies were born between 1940 and the end of the war (See Thorley Guide).

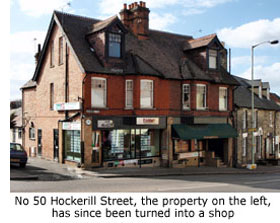

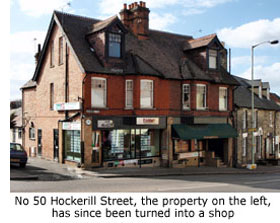

Most women were evacuated when nearing the end of their pregnancy, those sent to Stortford being first accommodated either on local farms or at No 50 Hockerill Street until the time came to enter Twyford House and give birth. Locals with their sense of humour still intact renamed Pig Lane, Pudding Lane. Most women were evacuated when nearing the end of their pregnancy, those sent to Stortford being first accommodated either on local farms or at No 50 Hockerill Street until the time came to enter Twyford House and give birth. Locals with their sense of humour still intact renamed Pig Lane, Pudding Lane.

Norwich had its first raid on 9 July, the Coleman's Mustard factory being hit and several workers losing their lives.

On 23 July, more than 1,300,000 Local Defence Volunteers had their name changed to Home Guard – the headquarters of Bishop's Stortford's Home Guard being the Drill Hall at Market Square (See Market Square – Guide 2). Thorley’s Home Guard headquarters was at Oxford House, White Posts in Stortford, with nearby Twyford Mill used as a base for one of its platoons commanded by Tom Streeter. Later promoted to Major Streeter and Company Commander he was ably assisted by Lieut. George Wilson, an ex naval man and signals expert who at that time owned a tobacconists in South Street.

Also announced on 23 July was the third War Budget: income tax increasing by 1d to 8s. 6d. (42 1/2p) in the pound, beer going up 1d a pint, and a 33% purchase tax introduced on luxury items.

July: Tea and margarine rationed

August Bank Holiday was officially cancelled this year but on 8 August, British Forces pay was increased by 6d per day putting a private's wage up to 17s 6d a week.

For Hitler's invasion of Britain – code-named 'Operation Sea Lion' – to succeed, German control of the air was vital to protect their invasion fleet. To this end, starting 10 July, the Luftwaffe probed for weaknesses, relentlessly attacking convoys in the channel, coastal towns, RDF stations, airfields and factories. Then on 8 August they implemented phase two of their strategy – to destroy the aircraft of Fighter Command on the ground or in the air.

Airfields in South East England including nearby Duxford and North Weald were constantly targeted, the daily wail of Stortford's air-raid sirens and the drone of approaching German bombers becoming an all too familiar sound to local people. Airfields in South East England including nearby Duxford and North Weald were constantly targeted, the daily wail of Stortford's air-raid sirens and the drone of approaching German bombers becoming an all too familiar sound to local people.

The bishop of Chelmsford at the time was Dr Henry Albert Wilson, a colourful and outspoken man whose strong opinions regularly featured in the monthly Chelmsford Diocesan Chronicle and also in the H&E Observer. He was of the opinion that the way in which the warning of an air raid was given was a psychological blunder. The old saying 'Whistle to keep your courage up is a scientific truth' he said, 'but the depressing wail of the air-raid siren was like the cry of a lost soul.' He thought its affect was profoundly bad on the individual, and though admitting to getting used to the wailing siren himself, he thought a warning which had a note of cheery defiance would save many people a great deal of unnecessary distress. To this end he suggested that a 'gay cock-a-doodle-do' repeated half-a-dozen times would be in the nature of a whistle to keep up the courage of the people. Needless to say his suggestion was ignored and the familiar wail of the sirens continued, as did German raids and air battles over Britain.

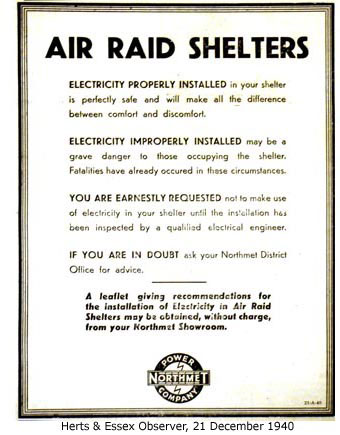

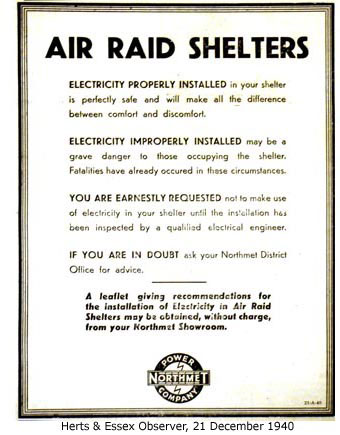

Vital to the public's safety at this time was the building of public air raid shelters, though in the town their provision by Bishop's Stortford UDC was always a contentious issue. The government may well have subsidised construction costs, but the council was always hard-pressed to find its share of the cash. The only solution was to take out a loan or increase the general rates, the latter option being chosen when £600 was needed towards the total cost of £1,710 for nine public shelters. This resulted in a twopence in the Pound increase on the half yearly rates.

To keep expenditure to a minimum the council later bought 200,000 second-hand bricks with which to build more shelters, but even then construction proved an ordeal. One proposal by the council for two communal shelters at the station was constantly delayed because, first and foremost, a site had to be determined in conjunction with the railway authorities. Design was also an issue but when two sites were finally agreed upon it was then found that a shortage of materials [other than bricks] meant that only one shelter could be built.

All public and communal shelters were brick-built surface type with concrete roofs. This design wasn't favoured for safety reasons and townspeople didn't want them, but they were quick and easy to construct so that's what they got. Public shelters were built at various points in the town including Market Square, Bridge Street and Portland Road – the latter being the largest with a reinforced concrete roof, three entrances, electric lights, and seating for up to 700 people. Waterside school at Water Lane, and Hockerill girls and boys schools at London Road were both fortunate enough to have a cellar converted for use as a shelter by pupils and staff. All other schools n the town had brick-built surface type shelters.

In the sky the battle for air supremacy continued, with dogfights between British and German fighters often taking place over Thorley. Bombs were also dropped on Thorley, sometimes randomly, including one night a Molotov basket of incendiary bombs that landed near to Moor Hall Cottages and lit up the sky for miles around.

By the middle of August, relentless attacks by the Luftwaffe had the RAF firmly on the back foot, and even more so when they switched to nighttime bombing of airfields and aircraft factories to delay repair and production. The turning point, however, came on the night of 23/24 August when bombs were accidentally dropped on London civilians – something Hitler had strictly forbidden. Bomber Command replied the following night by bombing Berlin, though the fear then was that British cities would now suffer even more raids. School children were once again evacuated to the safety of the countryside, including many of those who had returned home during the Phoney War period. By the middle of August, relentless attacks by the Luftwaffe had the RAF firmly on the back foot, and even more so when they switched to nighttime bombing of airfields and aircraft factories to delay repair and production. The turning point, however, came on the night of 23/24 August when bombs were accidentally dropped on London civilians – something Hitler had strictly forbidden. Bomber Command replied the following night by bombing Berlin, though the fear then was that British cities would now suffer even more raids. School children were once again evacuated to the safety of the countryside, including many of those who had returned home during the Phoney War period.

The first high explosive bomb to fall on Hertfordshire was at London Colney in June 1940. Bishop's Stortford experienced its first aerial bombardment on 31 August: several incendiaries causing damage to one house in the area but with no casualties. This isolated incident was probably the action of a marauding bomber.

Mass attacks on airfields and factories continued until 7 September, when Hitler, enraged by the bombing of Berlin and by the Luftwaffe's failure to destroy the RAF, turned his attention to London and other major cities in an attempt to demoralize the population and force Britain to come to terms. This was the beginning of the Blitz (short for Blitzkrieg), massed bombing raids that continued for the next consecutive 57 days and nights. *Civilians were constantly in the front line and casualties were high, but Hitler's change of tactics did give the RAF time to rebuild airfields, regroup, and deploy their own tactics that during daytime raids dealt heavy losses on the Luftwaffe.

*Between 7 September and 12 November, 13,000 tons of high explosive and about 1 million incendiary shells fell on London. 13,000 civilians were killed and more than 20,000 injured.

On 15 September, massive German air raids took place on London, Southampton, Bristol, Cardiff, Liverpool and Manchester. The market town of Bishop's Stortford was somewhat more fortunate with just two isolated bombings this month. Local people would have been fully aware of where the bombs dropped but because censorship forbid newspapers to specify where war related damage or casualties occurred, newspaper reports of enemy action were always ambiguous. In reference to the local raid on 16/17 September, the H&E Observer (dated 21 September) reported the following: Lone German raiders were flying almost continually over one district in Eastern England throughout Monday night and the early hours of Tuesday morning. Bombs were scattered over a wide area but damage was confined to two villages.

The local ARP report of the same bombings was a little more succinct: 17 Sept 1940: Several High explosives in fields east and west of Bishop's Stortford, no damage, no casualties.

On 20 September, Viscount Hampden officially opened the town's new police station in High Street, to which provision had been made (by an electrician) to install an additional siren for the town on its roof at a cost of £47. Half of this amount would be met by government grant.

That same day ARP recorded: 1 High explosives north of Bishop's Stortford, no damage, no casualties.

The H&E Observer, dated 21 September, carried all the general local news including fund raising events, local sport reports and details of Petty Sessions hearings. It also included the following rather amusing report:

A German pilot gave a five-mark note on Sunday 7 September 1940 to the mayor of Chatham's Spitfire Fund. The pilot, who had been shot down by RAF fighters of Kent earlier in the day, was being escorted under armed guard by train through Chatham. The train pulled up with the pilot's compartment opposite the refreshment buffet. A waitress held out her Spitfire Fund collecting box, and the pilot, who was made to understand what the box was for, obtained his wallet from one of the escort and smilingly pushed a note into the box. It has been suggested that the note should be auctioned for the fund.

The last major bombing raid on Britain in daylight hours was 30 September

To instill fear in the wider population, towns and villages around major cities were often subjected to attack by lone German aircraft, and to random bombing – especially at night. Pilots unable to reach their targets due to anti-aircraft fire, bad weather or damage to their aircraft, regularly jettisoned their bombs wherever they thought damage might be caused. Never was the need to adhere to blackout regulations made more clear than when one captured German pilot told how they were ordered to drop bombs wherever they saw a glimmer of light. To instill fear in the wider population, towns and villages around major cities were often subjected to attack by lone German aircraft, and to random bombing – especially at night. Pilots unable to reach their targets due to anti-aircraft fire, bad weather or damage to their aircraft, regularly jettisoned their bombs wherever they thought damage might be caused. Never was the need to adhere to blackout regulations made more clear than when one captured German pilot told how they were ordered to drop bombs wherever they saw a glimmer of light.

This being the case it would seem that Bishop’s Stortford was extremely lucky not to be bombed more frequently. For despite vigilant ARP wardens barking the order to ‘Put that light out’, many residents took no heed. Testimony to this is the large number of fines regularly imposed by Magistrate on individuals who didn’t comply with *blackout regulations.

*In 1940, 300,000 people nationwide were taken to court for blackout offences

Even so, the town was a veritable haven when compared to London’s war-torn East End and soon became a popular destination for firms wanting to get away from the Blitz. One such firm was a cork making factory that had been resident in London's East End since the 1800s. Owned by a Mr T Briggs of Portland Road, and before him his father, he not only moved his business to Stortford but also his employees and their families, setting up a factory at Anchor Yard (See Guide 11 – Riverside).

Also to arrive here from London's East End at that time was a small processing plant, absolutely vital to the war effort. This was the London Hospital (Ligature Department) Ltd, responsible for the production of catgut used for suture after operations and for wounds. Demand for the product greatly increased when war broke out, so to protect the costly equipment used for the final process both plant and staff were moved here for the duration of the war and production continued in the club-house of Bishop's Stortford Golf Club (See Guide 10 – Brooke Gardens).

British civilian casualties for the month of September: 6,954 dead, 10,615 injured

On 3 October Neville Chamberlain resigned from the War Cabinet, and on 7 October German troops entered Romania. Winston Churchill became leader of the Conservative Party

Safe haven or not, with ever more German bombing raids on Britain it was clear that those residents of Bishop’s Stortford with no domestic shelter of their own would need protection. The council’s response was a community shelter scheme costing an estimated £11,640, of which the council was expected to contribute £2,000. But as work on the project began so too did the bombing, marking October as the most memorable month in Bishop's Stortford’s war. ARP, who was required to record all bombing incidents, filed more reports this month than any other. The following (in bold type) are some of them.

8 October 1940: 3 high explosives at Foxdells Farm, half a mile NW of Bishop's Stortford, no damage, no casualties.

It may well have been this incident that prompted Tresham Gilbey, who lived at Whitehall, to build an air raid shelter in the middle of a field at nearby Dane O Coys. The remains of the shelter are still visible (See Guide 5 – Dane 'O Coys).

9 October 1940: 5 high explosives couple of miles WNW of Bishop's Stortford, no damage or casualties.

10 Oct 1940: 3 high explosives in fields at Wickham Hall, no damage or casualties;

3 high explosives in Bishop's Stortford, 2 in Girls Training College, 1 house demolished, 3 girls killed, road blocked.

The latter incident caused Bishop’s Stortford's only recorded deaths by direct bombing during the entire war. Reports since that time have varied as to exactly what happened that night. Some suggest it was random bombing, while others believe a marauding aircraft was trying to destroy a train travelling on the nearby branch line. Three bombs were dropped, the first hitting the Dunmow Road outside the college causing a large crater and damage to gas and water mains. Of the two remaining bombs, one exploded in open ground but the other made a direct hit on Menet House – accommodation within the college grounds used by students and staff. Three girl students were killed instantly. Rescue services worked through the night to free seven other students and a ecturer trapped in the rubble. One member of the rescue services, John Jarvis, later told how the building had imploded and that the bodies of the three girls were found sitting in armchairs completely grey from the blast.

16 Oct 1940: 5 high explosives one mile north of Bishop's Stortford, no damage or casualties; 8 high explosives in northern outskirts of Bishop's Stortford, no damage or casualties.

18 Oct 1940: 1 high explosive south side of Bishop's Stortford, damage to72 houses, no casualties.

21 Oct 1940: 1 oil incendiary at Bishop's Stortford, no damage or casualties;

1 high explosive at Woodside Green, Bishop's Stortford - 2 houses and outbuildings damaged, no casualties.

28 Oct 1940: 20 high explosives south and SE of Bishop's Stortford, damage to farm property and Haymeads Emergency Hospital and to wall of South Mill Lock on Stort Navigation - 1 man seriously injured, 5 men slightly injured.

30 Oct 1940: several high explosives north east of Bishop's Stortford near Stansted Road, damage to telephone wires, electric cable and house, no casualties.

British civilian casualty figures for October: 6,334 killed and 8,695 seriously injured

During September and October, two German aircraft crashed in the Bishop's Stortford area: one at Thorley Wash the other on the very edge of town, close to St Michael's church. During September and October, two German aircraft crashed in the Bishop's Stortford area: one at Thorley Wash the other on the very edge of town, close to St Michael's church.

The following details of the Thorley Wash crash are taken from 'WAR-TORN SKIES – Hertforshire' by Julian Evan-Hart.

The crash occurred at 23.40 hrs on Thursday 19 September. Whilst flying over its London target, a Heinkel He 111 is thought to have sustained damage by anti-aircraft fire. The pilot flew on, but the aircraft lost height and disintegrated in the air just before impact in marshy ground at Thorley Wash. Three crew members were killed and one was seriously injured. He survived. On crashing, the plane's tail broke away and landed at Latchmore Bank, the wings and fuel tanks lay at the side of the main A11 road (now the B183), and the engines and cockpit came down near the river Stort. The bomb load was still on board when the plane crashed and up until the 1960s the tip of a propeller blade could still be seen protruding from the marsh during winter when the reeds died away.

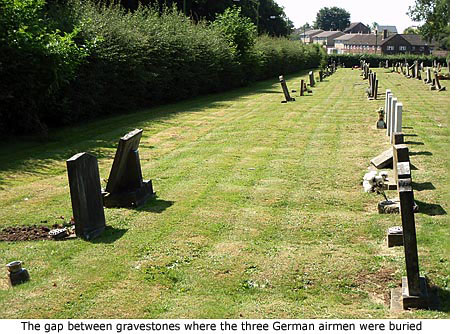

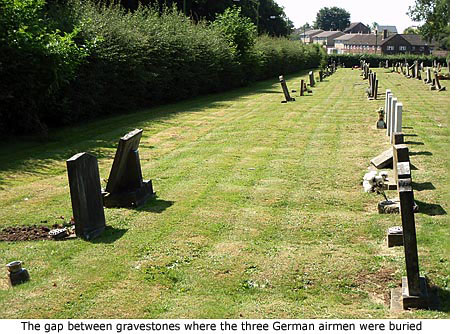

Even now evidence of the wreckage can still be seen at the crash site, since an oily patch shows through when the field floods. The remains of the three bodies were among the first to be buried in the newly constructed cemetery at Havers, but after the war were removed and laid to rest in Saffron Walden cemetery. To this day the plot of land in which they were buried at Havers has never been used and remains a gap between between gravestones. The only reminder of the three airmen is in an entry in the Bishop's Stortford cemetery register. Even now evidence of the wreckage can still be seen at the crash site, since an oily patch shows through when the field floods. The remains of the three bodies were among the first to be buried in the newly constructed cemetery at Havers, but after the war were removed and laid to rest in Saffron Walden cemetery. To this day the plot of land in which they were buried at Havers has never been used and remains a gap between between gravestones. The only reminder of the three airmen is in an entry in the Bishop's Stortford cemetery register.

The second crash occurred on Wednesday 16 October. A general report in the H&E Observer of enemy action 'in the Home Counties' that week, did mention the crash but gave no details of the location. Local people, however, certainly knew where the aircraft came down. The newspaper's report was as follows:

On Wednesday, for the second night in succession, people in a Home Counties town witnessed the end of a German raider. About 7 o'clock in the evening soon after the 'alert' siren had sounded, a 'plane was heard flying very low across the town. Seconds later terrific sheets of flame lit up the whole town as the 'plane, a Junkers 88, crashed by the side of a road, splitting into pieces. The local fire brigade attended and for over an hour flames leapt into the sky, while over-head could be heard the roar of night fighters. The crew perished with their machine, and it is known that at least three were blown to pieces. A burnt parachute was found in a nearby tree, but it is not known whether anybody had attempted to make a parachute descent. Official reports state that the bomber was brought down by anti-aircraft fire.

Julian Evan-Hart's research has since revealed further details of the crash.

The crash occurred at 19.50 hrs on Wednesday 16 October 1940. A large explosion was seen and heard in the sky above Stortford, followed by a second explosion as a Junkers JU88A-5 crashed into the ground in the vicinity of St Michael's church, near Great Hadham Road. The cause of the explosion in the air is unknown as no local anti-aircraft (AA) fire or sounds of attack by a night fighter were heard in the area. It appeared more likely the aircraft was hit by local AA fire some distance away and any damage later caused it to explode. Much of the debris was spread across Cable Field (now College Fields) and land bordering the Great Hadham Road. The remains of some crew members were found in a large Chestnut tree, along with shredded and partly deployed parachutes. The tree still remains, though the site of the crash has since disappeared under a housing estate built in the 1990s.

By the end of October, as the weather worsened, the Germans finally realised that the RAF couldn't be defeated. Hitler postponed his invasion of Britain indefinitely, turning his attention to Russia instead. The Battle of Britain was over but the bombing of London and other major cities continued until 11 May 1941, as did random bombing and enemy attacks by lone marauding German aircraft, locally.

ARP report for 8 Nov 1940 records:

25 high explosives at Woodside Green, two miles west of Bishop's Stortford, no damage or casualties.

Also that month the H&E Observer reported 'Dogfight Over Town After Daylight Raid'. No specific detail was given but we can assume the 'town' was Bishop’s Stortford. The report told how a hospital in the Home Counties was the victim of a lone bomber who came out of low clouds from the direction of London. Prior to releasing 10 high explosive bombs, the plane sustained damage from an attacking patrolling fighter aircraft. Nine of the bombs fell in an adjoining field, while the tenth demolished part of a new hutment that was being erected. Several workmen received light injuries, including one who was temporarily buried in the ditch he was digging. His friend who was standing within a few feet of where the bomb exploded wasn't even scratched but was more concerned about his lunch, which had been buried under a pile of debris. Hospital staff who had rushed to their aid, stood bemused as the workman let out a volley of expletives at the loss of his sandwiches.

Not reported in the paper was the crash of a Hawker Hurricane in Bishop’s Stortford on 24 November, though whether caused by accident or enemy action is unkown (by me).

Since the start of war, evacuees had increased the town's population by 50 percent, with 2,700 extra people arriving since July of 1940. This raised concern that not enough public shelters were available for the town's growing population, though complaints were counteracted by the publics indifference to air raids. Despite the danger a great many people didn’t bother to take cover during daytime warnings, leaving shelters almost empty. This lack of concern was also shown by the town’s *cinema goers. The slide caption ‘The Air Raid Siren has just been sounded, the show will continue for those wishing to stay’ became an all to familiar interference and most people continued to watch the film they had paid to see. Since the start of war, evacuees had increased the town's population by 50 percent, with 2,700 extra people arriving since July of 1940. This raised concern that not enough public shelters were available for the town's growing population, though complaints were counteracted by the publics indifference to air raids. Despite the danger a great many people didn’t bother to take cover during daytime warnings, leaving shelters almost empty. This lack of concern was also shown by the town’s *cinema goers. The slide caption ‘The Air Raid Siren has just been sounded, the show will continue for those wishing to stay’ became an all to familiar interference and most people continued to watch the film they had paid to see.

*Matinees for children at special charges were introduced on Thursdays and Saturdays and later in 1940 on Wednesday afternoons also. One of the most popular films shown in 1940 was ‘The Wizard of Oz.’

Nighttime air raid warnings were a little different, many people taking cover in shelters and then sleeping in them all night. This included entire families from London who travelled here by train or by car – a practice that had been going on since the start of the Blitz in September. Another issue was the disgusting state that shelters were left in after the public had used them, and vandalism to fittings.

Despite all this, seven public shelters were now to have sleeping accommodation while no fewer than 108 extra communal shelters were to be built at a cost of not less than £16,000. The argument against surface shelters continued though, one council members suggesting that an underground shelter be built at South Lawn in South Street to accommodate people living in that densely populated area. When it was pointed out that the sub soil in Stortford wasn't suitable for the construction of such a shelter, it was then suggested that unemployed miners should be hired to excavate the site. Needless to say, deep shelters were finally ruled out.

British civilian casualty figures for November: 4,588 killed, 6,202 injured

There were no public shelters in Thorley but each household had its own shelter, be it Anderson or Morrison. The problem was, the town’s air-raid siren couldn’t always be heard at Thorley Park so residents suggested that Featherby’s in London Road sounded their factory hooter whenever a raid was imminent. Whether or not this option was in place by 8 December is unknown but at 5.40 that evening, Stortford’s air-raid alert sounded and not until thirteen-and-a-half-hours later was the all-clear given.

Local ARP report for 9 December 1940:

1 high explosive 550 yards north of the station at Bishop's Stortford, no damage or casualties.

Christmas Day was celebrated as normal but Boxing Day Bank Holiday was officially cancelled. The night of 29/30 December saw the most devastating raids to date on London's East End and docks.

British civilian casualties figures for December: 3,793 killed, 5,244 injured

|

On 6 February the 'Careless Talk Costs Lives' campaign was launched; on 22 February two IRA bombs exploded in London, and on 11 March all meat was rationed.

On 6 February the 'Careless Talk Costs Lives' campaign was launched; on 22 February two IRA bombs exploded in London, and on 11 March all meat was rationed. Nazi Germany's surprise invasion of the Low Countries and France, outnumbered and so overwhelmed the British Expeditionary Force that they were forced to retreat back to the small Channel port of Dunkirk where they remained trapped on the beaches. The subsequent evacuation by the Royal Navy, starting on 26 May, of over 338,000 Allied troops back to England also owed much to civilians in their 'little boats', but all of the expeditionary force's military hardware was lost.

Nazi Germany's surprise invasion of the Low Countries and France, outnumbered and so overwhelmed the British Expeditionary Force that they were forced to retreat back to the small Channel port of Dunkirk where they remained trapped on the beaches. The subsequent evacuation by the Royal Navy, starting on 26 May, of over 338,000 Allied troops back to England also owed much to civilians in their 'little boats', but all of the expeditionary force's military hardware was lost. In fact, Britain was now extremely vulnerable to attack by the Luftwaffe. The battle for France had left Fighter Command with just 768 planes in operational squadrons, of which only 520 were fit for operations. Matters weren't helped by replacement aircraft from North America taking so long to produce, forcing Britain to fight with only what its own factories could produce.

In fact, Britain was now extremely vulnerable to attack by the Luftwaffe. The battle for France had left Fighter Command with just 768 planes in operational squadrons, of which only 520 were fit for operations. Matters weren't helped by replacement aircraft from North America taking so long to produce, forcing Britain to fight with only what its own factories could produce. Haymeads hospital became an annexe for the London Hospital, caring for walking wounded soldiers, at the same time being expanded to take casualties from any future bombing. The chance of London hospitals being bombed at this time was extremely high, so to protect expectant mothers the War Office requisitioned many large properties outside of London for use as maternity hospitals. Locally, this included *Twyford House at Pig Lane, where it is said 693 babies were born between 1940 and the end of the war (See Thorley Guide).

Haymeads hospital became an annexe for the London Hospital, caring for walking wounded soldiers, at the same time being expanded to take casualties from any future bombing. The chance of London hospitals being bombed at this time was extremely high, so to protect expectant mothers the War Office requisitioned many large properties outside of London for use as maternity hospitals. Locally, this included *Twyford House at Pig Lane, where it is said 693 babies were born between 1940 and the end of the war (See Thorley Guide). Most women were evacuated when nearing the end of their pregnancy, those sent to Stortford being first accommodated either on local farms or at No 50 Hockerill Street until the time came to enter Twyford House and give birth. Locals with their sense of humour still intact renamed Pig Lane, Pudding Lane.

Most women were evacuated when nearing the end of their pregnancy, those sent to Stortford being first accommodated either on local farms or at No 50 Hockerill Street until the time came to enter Twyford House and give birth. Locals with their sense of humour still intact renamed Pig Lane, Pudding Lane. Airfields in South East England including nearby Duxford and North Weald were constantly targeted, the daily wail of Stortford's air-raid sirens and the drone of approaching German bombers becoming an all too familiar sound to local people.

Airfields in South East England including nearby Duxford and North Weald were constantly targeted, the daily wail of Stortford's air-raid sirens and the drone of approaching German bombers becoming an all too familiar sound to local people. By the middle of August, relentless attacks by the Luftwaffe had the RAF firmly on the back foot, and even more so when they switched to nighttime bombing of airfields and aircraft factories to delay repair and production. The turning point, however, came on the night of 23/24 August when bombs were accidentally dropped on London civilians – something Hitler had strictly forbidden. Bomber Command replied the following night by bombing Berlin, though the fear then was that British cities would now suffer even more raids. School children were once again evacuated to the safety of the countryside, including many of those who had returned home during the Phoney War period.

By the middle of August, relentless attacks by the Luftwaffe had the RAF firmly on the back foot, and even more so when they switched to nighttime bombing of airfields and aircraft factories to delay repair and production. The turning point, however, came on the night of 23/24 August when bombs were accidentally dropped on London civilians – something Hitler had strictly forbidden. Bomber Command replied the following night by bombing Berlin, though the fear then was that British cities would now suffer even more raids. School children were once again evacuated to the safety of the countryside, including many of those who had returned home during the Phoney War period. To instill fear in the wider population, towns and villages around major cities were often subjected to attack by lone German aircraft, and to random bombing – especially at night. Pilots unable to reach their targets due to anti-aircraft fire, bad weather or damage to their aircraft, regularly jettisoned their bombs wherever they thought damage might be caused. Never was the need to adhere to blackout regulations made more clear than when one captured German pilot told how they were ordered to drop bombs wherever they saw a glimmer of light.

To instill fear in the wider population, towns and villages around major cities were often subjected to attack by lone German aircraft, and to random bombing – especially at night. Pilots unable to reach their targets due to anti-aircraft fire, bad weather or damage to their aircraft, regularly jettisoned their bombs wherever they thought damage might be caused. Never was the need to adhere to blackout regulations made more clear than when one captured German pilot told how they were ordered to drop bombs wherever they saw a glimmer of light. During September and October, two German aircraft crashed in the Bishop's Stortford area: one at Thorley Wash the other on the very edge of town, close to St Michael's church.

During September and October, two German aircraft crashed in the Bishop's Stortford area: one at Thorley Wash the other on the very edge of town, close to St Michael's church. Even now evidence of the wreckage can still be seen at the crash site, since an oily patch shows through when the field floods. The remains of the three bodies were among the first to be buried in the newly constructed cemetery at Havers, but after the war were removed and laid to rest in Saffron Walden cemetery. To this day the plot of land in which they were buried at Havers has never been used and remains a gap between between gravestones. The only reminder of the three airmen is in an entry in the Bishop's Stortford cemetery register.

Even now evidence of the wreckage can still be seen at the crash site, since an oily patch shows through when the field floods. The remains of the three bodies were among the first to be buried in the newly constructed cemetery at Havers, but after the war were removed and laid to rest in Saffron Walden cemetery. To this day the plot of land in which they were buried at Havers has never been used and remains a gap between between gravestones. The only reminder of the three airmen is in an entry in the Bishop's Stortford cemetery register.

Since the start of war, evacuees had increased the town's population by 50 percent, with 2,700 extra people arriving since July of 1940. This raised concern that not enough public shelters were available for the town's growing population, though complaints were counteracted by the publics indifference to air raids. Despite the danger a great many people didn’t bother to take cover during daytime warnings, leaving shelters almost empty. This lack of concern was also shown by the town’s *cinema goers. The slide caption ‘The Air Raid Siren has just been sounded, the show will continue for those wishing to stay’ became an all to familiar interference and most people continued to watch the film they had paid to see.

Since the start of war, evacuees had increased the town's population by 50 percent, with 2,700 extra people arriving since July of 1940. This raised concern that not enough public shelters were available for the town's growing population, though complaints were counteracted by the publics indifference to air raids. Despite the danger a great many people didn’t bother to take cover during daytime warnings, leaving shelters almost empty. This lack of concern was also shown by the town’s *cinema goers. The slide caption ‘The Air Raid Siren has just been sounded, the show will continue for those wishing to stay’ became an all to familiar interference and most people continued to watch the film they had paid to see.