|

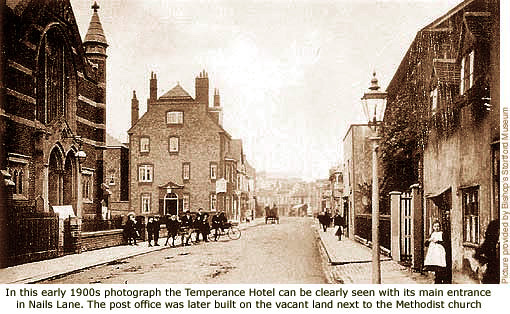

One of the more prominent buildings in South Street is the former Albert Temperance Hotel, erected around the turn of the 20th century when the Temperance Movement was at its height. Interestingly, plans for the building of this hotel were submitted to the council in 1898 on behalf of Sir Walter Gilbey, and passed immediately. The only proviso was that the side street alongside (*Nails Lane) should be used solely for access to the hotel. Considering Gilbey made his initial fortune selling wines and spirits to the public, it's doubtful he built this hotel in support of the Temperance Movement. More likely it was a shrewd move into the property market. When the hotel ceased to be a 'dry' house is unknown, but it finally closed in the 1950s. Its entrance in Nails Lane was later removed to accommodate a shop frontage.

*Nails Lane was the name given to the roadway alongside the hotel that once led to the old telephone exchange and other small businesses, though why it was called as such is anybody's guess. After redevelopment of the area in the early 1990s, no properties in need of an address were left standing and so Nails Lane disappeared.

In the beginning temperance was a half-hearted affair, members promising not to drink spirits but continuing to drink wine and beer. This minor hiccup in their doctrine was ammended in the 1840s when temperance societies began advocating tee-totalism; not only a pledge to abstain from alcohol for life, but also a promise not to provide it to others. It was this that led to the building of countless ‘dry houses’ throughout the country – otherwise known as Temperance Hotels. Added support came with the founding of the British Women’s Temperance Society, whose sole aim was to persuade men not to drink, and in 1847 a temperance organisation for working class children was formed in Leeds, known as the Band of Hope. It was this organisation that ultimately helped increase the number of abstainers.

For most people, drink was the only refuge from the misery of poverty, as well as being a cheap substitute for water and milk – both of which were generally unsafe to drink at that time. In the late 19th century it was estimated that more than a quarter of the daily earnings of working class people was spent on alcohol. For most people, drink was the only refuge from the misery of poverty, as well as being a cheap substitute for water and milk – both of which were generally unsafe to drink at that time. In the late 19th century it was estimated that more than a quarter of the daily earnings of working class people was spent on alcohol.

The Temperance Movement had been fairly prominent in Bishop's Stortford since its beginnings, evidence of which comes from a poem published in July 1843 that condemned drink and every public house in Stortford (See Guide 10). It remained fairly active thereafter but temperance was a brave objective in a town employed largely in the malting and brewing industry. By the end of the 19th century temperance had generated a lot of anger among workers at Benskins Brewery in Water Lane.

One local man, Joseph Crisp, a staunch supporter of temperance and owner of a drapery shop in Market Square, was nicknamed ‘Jesus’ Crisp. He regularly antagonised brewery workers for their association with drink, but after over-stepping the mark once too often his shop window was completely covered in tar.

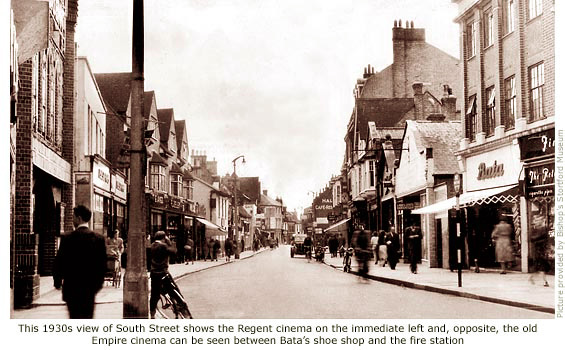

Two other prominent town citizens, and devout believers in temperance, were Joseph Dorrington Day and Alfred Slapps Barrett, the latter founding the Pleasant Sunday Afternoon Club. This semi religious gathering, which barred women, was set up to give men 'something to do' on a Sunday afternoon. Meetings were first held in the Working Men’s Club, then between 1903 and 1911 in the disused Wesleyan Chapel at No 1 South Street.

The local Movement also arranged town outings for its members – the sixth annual Temperance outing to Walton-on-the-Naze in 1888 attended by a record 600 total abstainers. This figure does seem somewhat excessive and it's likely that many people only claimed to be abstainers in order to get a day out by the sea.

Temperance was also strong within the Church of England. In 1900 a Mr G. Avery Rolf, lecturing Hockerill College students, told them that alcohol should be taken only on prescription and administered by a doctor. He also warned of the effects on elementary school children of intemperate parents, a theory echoed by local man Joseph Dorrington Day, who used a picture of a serpent curled up in a wine glass to illustrate the evils of drink to Sunday school children.

Although support for the town’s Temperance Movement finally dried up after the deaths of its most prominent local supporters, the hotel remained in business until the 1950s.

MORE PICTURES

|

For most people, drink was the only refuge from the misery of poverty, as well as being a cheap substitute for water and milk – both of which were generally unsafe to drink at that time. In the late 19th century it was estimated that more than a quarter of the daily earnings of working class people was spent on alcohol.

For most people, drink was the only refuge from the misery of poverty, as well as being a cheap substitute for water and milk – both of which were generally unsafe to drink at that time. In the late 19th century it was estimated that more than a quarter of the daily earnings of working class people was spent on alcohol.