|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It is known there were two vicars at St Michael’s before the first was recorded in 1332, and up to the present day (2007) there have been 57 in total. Among the many notable names was Richard Fletcher (c.1523–1586), one of the first clergymen ordained according to the protestant ordinal. A Cambridge graduate from York diocese, he (along with John Foxe) was ordained deacon by Nicholas Ridley, bishop of London, in June 1550, and priested in November the same year.

He became vicar of Bishop's Stortford in 1551, but under the rule of Mary Tudor was forcibly removed by bishop Bonner in 1554 because he was married. There is no evidence to support the tradition that he took his family abroad to escape further persecution: indeed, in July 1555 he and his son – also Richard Fletcher (1544–1596) – witnessed the martyrdom of Christopher Wade at Dartford, Kent, subsequently both signing an account which John Foxe included in the second edition of Acts and Monuments (1576).

After Elizabeth's accession both Richard Fletchers gained the patronage of Matthew Parker, archbishop of Canterbury, who in 1561 collated the elder Richard to the vicarage of Cranbrook, Kent, and in 1566 to the nearby rectory of Smarden. The young Richard was admitted pensioner at Trinity College, Cambridge in 1562, and scholar in 1563, graduating BA in 1566. He became a fellow of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge in 1569, being ordained deacon and priest that same year.

In 1583 he was installed dean of Peterborough and was intimately involved in the trial and execution of Mary, queen of Scots at Fotheringhay in 1586/7. He was made bishop of Bristol in 1589 and bishop of London in 1595. Fletcher's life-long addiction to tobacco finally ended his days on 15 June 1596. After returning to his Chelsea home and smoking his familiar pipe he suddenly exclaimed to his servant, 'Boy, I die' and did so. He was buried in St Paul's Cathedral without any memorial.

*Richard Fletcher jnr's son, John Fletcher (1579–1625), was one of the great dramatists of Jacobean London. His contemporaries included Thomas Kyd, Christopher Marlowe, Ben Jonson, and Francis Beaumont – all of whom produced works still performed today.

Born at Rye, in Sussex, and educated at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge (as was Christopher Marlowe), Fletcher first collaborated with Francis Beaumont (1584–1616) producing romantic tragicomedies. It is thought William Shakespeare (1564–1616) may well have supervised and edited their early work, and is known to have admired Fletcher's style. He also collaborated with him on his last three plays, Cardinio, The Life of King Henry the Eighth, and The Two Noble Kinsmen – all written and produced in 1613-14. In the 1612/13 season, he shared Shakespeare's fortune at Court; Shakespeare having had nine plays performed and Fletcher having eight.

Beaumont married in 1613 and ceased writing, but Fletcher continued to have great success collaborating with Johnson and Massinger. It is estimated that between 1609 and the time of his death, Fletcher was involved in writing forty-two plays. He died of the plague in 1625 and is buried in Southwark Cathedral, London.

Francis Burlye (1590–1604) was vicar of both St Michael’s and St James at Thorley, and was one of a group of scholars who helped produce the Authorised Version of the Bible for King James I. John Payne (1651–1662) was removed in 1662 for refusing to subscribe to the restored religion. The most memorable name from the 1800s was Francis William Rhodes, father of Cecil Rhodes the founder of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). Of vicars in the last century: *Edgar Killick had played cricket for Middlesex and was twice selected for England against South Africa; Charles Hooper became Archdeacon of Ipswich, and David Farmbrough became Archdeacon of St Albans and later Bishop of Bedford.

*Rev Edgar Thomas Killick was ordained in 1936 and came to St Michael's in 1946. Aged 46, he collapsed and died in May 1953 while playing cricket for St Albans diocese in a match against Coventry diocese.

COMPLETE LIST OF THE VICARS OF ST MICHAEL'S

In 1845 the church was transferred from the Diocese of London to the Diocese of Rochester, and in 1867 to the newly formed Diocese of St Albans where it remains to this day.

|

|

|

|

|

|

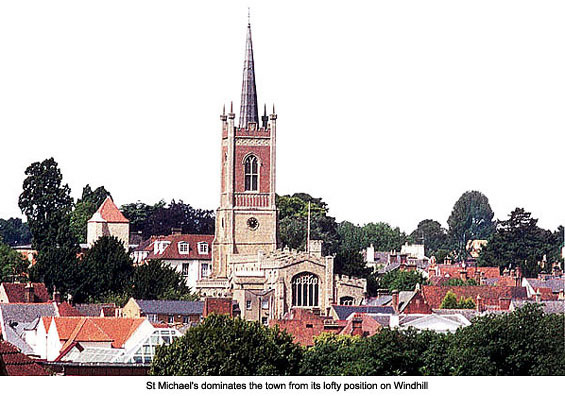

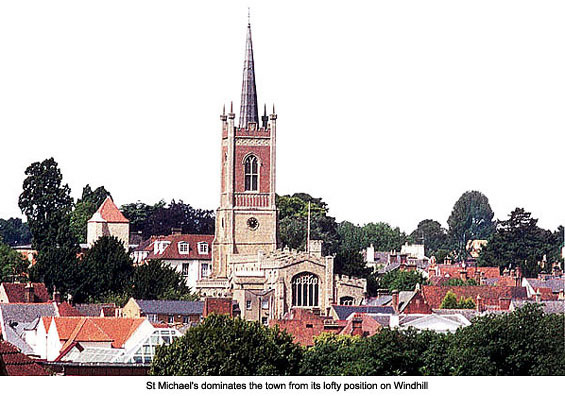

In the 18th century alterations were made to the interior of the church and minor repairs to the outside, but by the 19th century major restoration work was urgently required. The original lofty spire and part of the 15th century tower was in imminent danger of collapse and an Act of Parliament was needed, and granted, for the work to be carried out. Between 1812 and 1819 a new belfry was added to the tower and a new slate-clad spire erected. Those same slates were removed in 1970 and replaced by a lead covering. The spire, standing 185ft (56 metres) high, is still the most prominent landmark in Bishop’s Stortford, seen from virtually every part of the town and surrounding area. But not everybody, it seems, was happy with the new tower. 19th century graffiti inside it reads: ‘This tower was built by Parish expense, but a mean Parish that gives the workers nothing to drink’. In the following years many other alterations were made including, in 1863, the removal of the external plaster to reveal the original flint walls.

It isn’t known when there were first bells in St Michael’s but churchwardens’ accounts for 1439 show the tower contained five at that time. These were later replaced by five new ones, ordered in 1489 from a foundry in Bury St Edmunds at a cost of £42. Up until 1530 the bells were repaired and sometimes replaced by a foundry in London. It was those bells that rang out when Queen Elizabeth I was crowned in 1558, and again when the Spanish Armada was defeated in 1588. On the latter occasion, ringers were rewarded with ale and candles. Throughout the 17th century they rang out loud and clear to celebrate any event of national or local importance, including the coronations of James I in 1603, Charles II in 1661, and James II in 1685. In 1629 and 1630 they were rung to celebrate a visit to the town by Charles I and the fact that he ‘dyned at ye George’ in North Street.

In 1671 a sixth bell was added to the peal but by the 18th century, after so much use, all had to be recast. This task was carried out in 1713 by John Waylett (See Guide 5 – Bells Hill), a local bell founder who re-cast three of them and with the metal of the remaining three, cast five new bells making a ring of eight. He also cast a new bell in 1730. Another bell founder, John Briant, of Hertford, renewed two of the bells in 1791 and another in 1802. He also cast a funeral bell that same year. When the tower and spire were rebuilt in 1819, the bells were put into storage and a new wooden frame constructed in the belfry to accommodate ten bells. John Briant cast two new bells in 1820 and rehung all ten, the largest of which weighs 17cwt. It is these ten bells that constitute the present ring.

The first mechanical clocks appeared in this country during the 14th century, and a church clock was in place on the tower of St Michael's in 1431. Not being the most reliable of timepieces, however, it was replaced in 1494 by one with chimes. It must be remembered that in those days people didn’t have watches and the church clock was very important to them. Nor was there such a thing as ‘Greenwich Mean Time’ so clocks would only show an approximate time, which could differ by some considerable margin in towns throughout the country. What we now know as ‘Standard’ time wasn't available everywhere in Britain until the BBC started broadcasting the ‘six pips’ GMT time signal in 1924.

The same John Briant who cast six of the current church bells, also made and installed the clock on the east side of the tower in 1820. Those on the other three sides (all 5ft 6ins in diameter) were added by John Yardley in 1846, and were paid for with the aid of public subscription. Known as a 'bird cage' clock, and housed in a wooden casing on a floor between the belfry and the bell-chamber, the mechanism was originally driven by a pendulum 80 ft (24 metres) long and a lead weight weighing a quarter of a ton. It required winding by hand three times a week. The clock was regularly serviced, but on 5 August 2005, was totally removed for the first time in 185 years for repair and overhaul. The work, undertaken by A. James (Jewellers and Horologists) of Saffron Walden, took four weeks to complete and the cost of over £6,000 was funded by Friends of St Michael’s. When reinstalled, the clock was fitted with an automatic winder.

A weathercock was erected during Queen Mary’s reign (1553-58) at a cost of 21 shillings (£1. 05p), and in 1796 a large sundial, still in place, was fitted high up on the south wall. MORE PICTURES

|

|

[ BACK TO TOP ] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|